Episode 6: War of Air & Fire

The site of Gebo, Wyoming—location of the first known Fu-go balloon sighting—the land showing the scars of contemporary fires and the skies filled with smoke from California’s worst fire season on record.

Amid the astonishing destruction of World War II in Europe and Asia, the mainland of the United States had been spared from the ravages of this global conflict. While several isolated attacks took place on the coasts, the dictators in Berlin & Tokyo sought super weapons to use against the US.

For Japan, one of these super weapons came in the form of the Fu-go balloon project that involved launching 9,000 explosive laden balloons from Japan to the US.

En route to location of the first Fu-go balloon sighting and bombing, the skies of Wyoming were eerily yet fittingly stained by smoke from California’s worst ever fire season.

On the road to Thermopolis, the closest site to the first Fu-go sighting of any significance on a map.

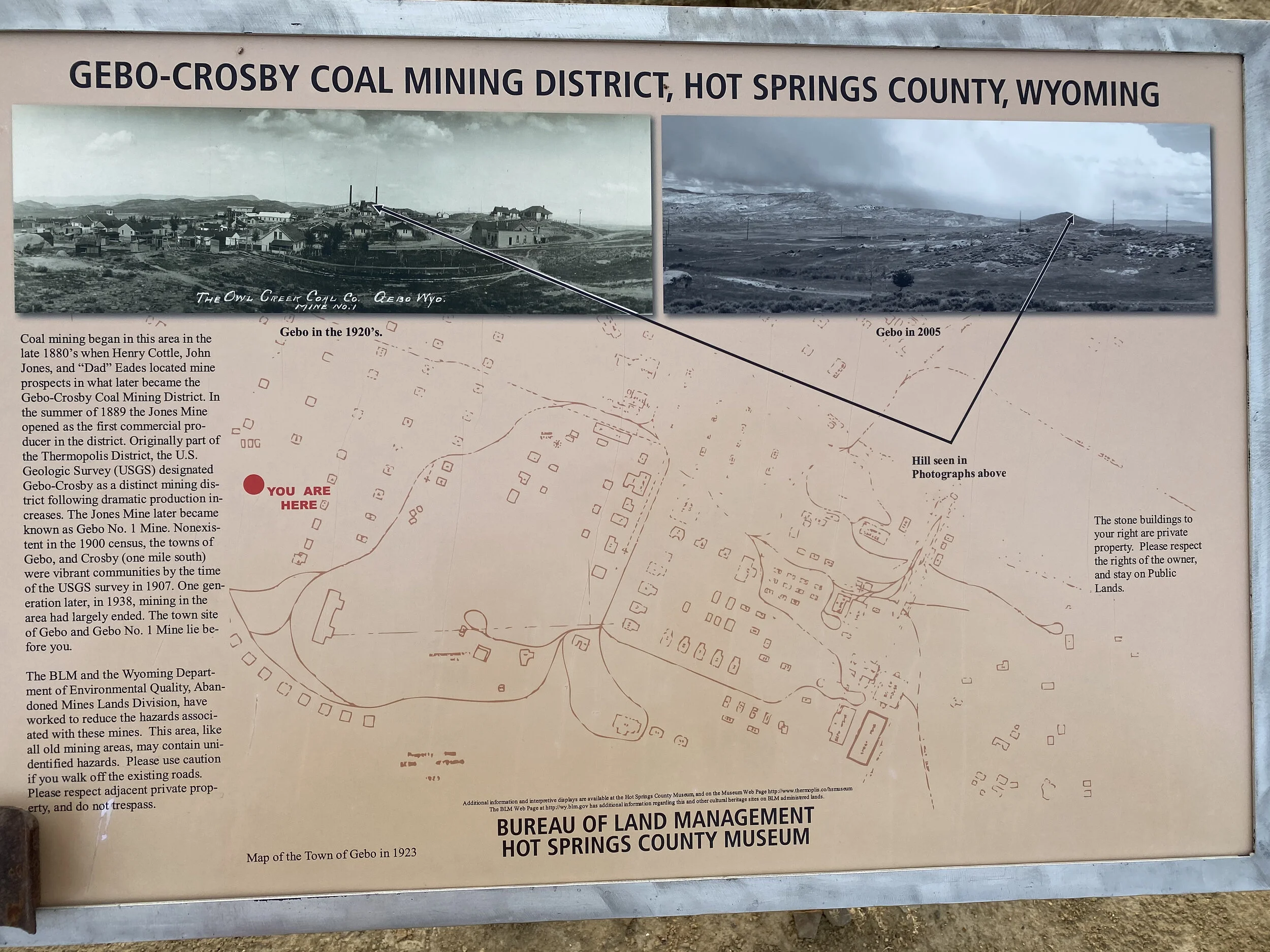

Map of the remnants of the small mining town of Gebo, Wyoming, the location of the first known sighting of Fu-go balloons.

Remnants of the small mining town of Gebo, Wyoming, the location of the first known sighting of Fu-go balloons.

Portrait of L. L. Zamenhof, Polish ophthalmologist and creator of the Esperanto language.

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jet stream clouds over Canada. Wasaburo Oishi published nineteen volumes of work in Esperanto on his findings about what he called the “equatorial smoke stream”.

NASA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustrated phenomena of the effects of the eruption of Krakatoa on the skies of London. At the time no one understood how the smoke spread so vastly, so quick.

71-1250, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wiley Post in the prototype pressurized suit made for him by the B.F. Goodrich tire company in an attempt to enable human flight at higher altitudes.

Unknown author, Smithsonian Institution, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The functional pressurized suit used by Wiley Post, which enabled him to fly at altitudes of 50,000 feet above sea level and observe the impact of the jet stream on the speed of flight.

SI 98-15012, Eric Long, Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, Copyright Smithsonian Institution, educational fair use under Section 108 of U.S. Copyright Act.

Fires ravaging Tokyo due to firebombing by B-29s on May 26, 1945.

US Army Air Forces, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

MF Thomas’ great-uncle Masamichi “Mac” Suzuki and great-aunt Zoe.

Fu-go balloon shot down over Alaska as shown on gun cameras.

11th Air Force Fighter. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Fu-go balloon found near Bigelow, Kansas with its bombs still attached in February 1945.

National Museum of the U.S. Navy. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Fu-go balloon mechanism recovered in California, including three incendiary bombs and six sand bags.

National Museum of the U.S. Navy. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Briefing of members of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, AKA the “Triple Nickels”, prior to take off. They were the only black parachute unit, and were the first black combat unit commanded by black officers in the U.S. Army since the Civil War.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Mitchell Monument near Bly, Oregon. It was built in remembrance of the six people killed in the only known deaths resulting from Fu-go balloons, as well as the only site in the continental U.S. where people died in direct result of enemy action in WWII.

United States Forest Service. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Full Script

INTRODUCTION

As I wrote the first episode for My Dark Path over a year ago, learning so much more about airships, that yet again, one of my assumptions about WWII was shattered. I had the poorly informed idea that the mainland of the United States had been spared from the ravages of the two great world wars. While oneoff attacks may have taken plan on the coasts and while dictators in Berlin & Tokyo had dreamed of striking at the US, nothing real, nothing material had ever come close to implementation. My attention hadn’t ever really considered the possibility that the mainland had been attacked, deliberately and consistently though fortunately without meaningful impact. The airship story revealed the history of the Fu-go balloons. These were explosive balloons, launched by the thousands, targeting the American continent. This was the Japanese strategy, in the war’s latter stages, designed to tip the momentum back in their favor. And, oddly, my research revealed the first known sighting was in Thermopolis Wyoming, just hours away from my grandmother’s birthplace and her family’s home.

So, as I made my way through the two-lane roads that make up much of the beautiful and varied terrain of Wyoming, I briefly regretted my decision to find the site of the first known arrival of this weapon. Other than some general directions, there was little documented about the specific location. The first hurdle was discovering that the site wasn’t near Thermopolis, but simply that it was the closest town with a meaningful name. In reality, it was near an abandoned mining town of Gebo – about an hour away from Thermopolis. This episode tells the story of the Fu-go balloons, what we learned in Gebo and, perhaps more importantly, what we learned about some of the amazing people whose personal histories are intertwined with these events.

***

Hi, my name’s MF Thomas; I’m an author and a lifelong fan of strange stories from the dark corners of the world. Growing up, I was enthralled by any hint of exciting, forbidden knowledge that waited behind the names and dates we learned in school. And these days, as I travel the world, there’s nothing I enjoy more than to get off the traditional tourist map and find a place or story that has been overlooked, dismissed or ignored.

In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these topics….you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. To see content related to every episode, visit MyDarkPath.com. As I’m recording this, I’m wearing an amazing My Dark Path t-shirt. I still have about 30 left – if you’d like one – leave a review or send me an email with a topic you’d like to see me cover. My email is explore@mydarkpath.com

And thank you, dear listener, for reaching out with your thoughts, feedback and encouragement. My dad, who has become a bit of a podcast junkie of late, called me last week after listening to the Val Johnson episode. After talking about the fun and challenging steps required for production of My Dark Path, I was able to feed back to him the mantra that he always shared with me and my siblings when embarking on something new, something difficult and uncertain, that this situation is, quote “just the way we like it.” Thanks for encouraging resilience Dad. And Dad, I promise that we’ll get to an episode about bigfoot and cryptids at some point...soon.

So, let’s begin with Episode 6, the War of Air & Fire.

PART ONE

“AL NIAJ BONAJ KAJ LEGALAJ TEMOJ”

(pronunciation: “ahl nee-aye boh-nye kye leh-jah-lye teh-moy”)

It’s okay if you don’t understand what I just said. I had to look up the pronunciation myself. The language I attempted to speak is Esperanto and the phrase means “To Our Good and Loyal Subjects.” More on the implications of this phrase later.

Unlike most languages, which develop organically in large populations over centuries, Esperanto was created by one person – a Polish ophthalmologist named L.L. Zamenhof, in 1887. His grand ambition was to create an easy-to-learn language that people all over the world could study as a secondary language, a way to build a bridge between nations and cultures. Zamenhof’s hope was that if we all studied one language beyond our native one, then any two people in the world could meet on common ground. He published his first book about his new language under the pseudonym “Doktoro Esperanto”. The word “Esperanto” translates into English as “one who hopes”.

Although Esperanto never caught on to the extent that Zamenhof hoped, it has attracted followers and admirers over the years. It’s estimated that as many as two million people speak the language today, and the British poet William Auld was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature for poetry that he wrote in Esperanto. From the beginning, it’s had a powerful effect on some people who aspire to bring the human race together. The language and the movement behind it has a fascinating and, unfortunately sad history. I never thought I’d say it, but it’s history has made of list of future episodes.

One early believer in Zamenhof’s vision was Wasaburo Oishi, a Japanese meteorologist in the early 20th Century. Oishi had been studying a phenomenon that no one in the world had yet to adequately explain. When the volcano on the island of Krakatoa erupted in 1883, smoke from the eruption was carried all over the world for years, disrupting weather patterns, changing the color of skies, even making the moon look blue, in some places. No one could explain how the smoke traveled so far quickly; even though everyone could see it happening. The phenomenon was called the “equatorial smoke stream”.

Oishi conducted research near Japan’s Mt. Fuji, another active volcano. He watched as pilot balloons – weather balloons designed to measure winds at high altitudes – started to rapidly accelerate when they reached a sufficient height; but only in particular areas. It was as if there was a highway up in the atmosphere, and these balloons were finding the express lane.

From 1926 to 1944 he published 19 reports on this phenomenon, meticulously measuring and describing it in over 1,246 pages. But for years, very few people were even aware of what he had discovered – because he published all 19 volumes in Esperanto. He was the Board President of the Japanese Esperanto Institute; an impassioned believer in the philosophy of Doktoro Esperanto.

What Oishi had discovered literally brings the world closer to this day. It’s what we now refer to as the jet stream – high-speed air currents that circle the world. Jet streams are created by the combination of the sun’s radiation with the rotational force of the Earth. To fly in the jet stream means you’re getting a powerful speed boost from the forces of nature. Today, commercial and military air travel takes into account the effects of various jet streams on time and fuel needs.

The person who really made the jet stream famous was an America pilot, Wiley Post. Post was a pioneering aviator on a par with Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh – in 1931 he set the record for circumnavigating the world in just 8 days, 15 hours, and 51 minutes. If you’ve listened to our first episode, you might recognize the person he took the record from – it was Hugo Eckener, flying the Graf Zeppelin.

Wiley Post believed that the secret to getting more and more speed in the air was to fly higher in the atmosphere, where the air is thinner. But the higher he went, the more hazardous it was to his health. When he couldn’t adequately pressurize the cockpit of his plane so he could breathe, he worked with employees of the B.F. Goodrich tire company to create a pressure suit that was strong enough to protect him, but also flexible enough for him to fly his plane. When you look at pictures of it now, it looks like the evolutionary missing link between an old diving suit, and a NASA spacesuit. There was nothing like it in the world at the time.

Inside his groundbreaking pressure suit, Wiley Post was able to fly up to altitudes no airplane pilot had ever seen before, as high as 50,000 feet above ground. And it was while he cruised at these heights that he noticed that there was an enormous discrepancy between the air speed on his instruments, and the speed he was traveling over the ground. As if he was being pushed by a massive, invisible wave.

The world was becoming aware of this powerful force, and how it could be used to cut the distance between far-flung places. And this knowledge was strategically important as the most powerful nations on Earth descended into the second World War.

In Japan, the home country of Wasaburo Oishi, the jet stream was the crucial ingredient in a plan to strike the United States. A plan that sounds so audacious and impossible that you can imagine it appearing in a sci-fi novel. But it was real, and it happened, though it’s rarely mentioned in most histories of World War II.

The Empire of Japan struck the United States, not just at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, but the continental mainland as well. They achieved what Hitler only fantasized about with his Amerika Rakete; crossing the ocean to assault an enemy from thousands of miles away. But they didn’t do it with rockets, or any kind of radical new technology. They did it with the simplest of elements – air, and fire. When Japan succeeded in attacking the mainland, they did it with balloons. They were known as the Fu-Go Balloon Bombs, a weapon that was both ingeniously simple and horrifying in its intentions.

The Fu-Go Balloon campaign came very late in the war, when Japan had lost all of its strategic position in the ocean, and was facing the prospect of a land invasion by Allied Forces. Like Hitler’s “Vengeance Weapons”, they represented a last, desperate hope to turn the tables, and strike a psychological blow by terrorizing our civilian population. In the Japanese culture, fire is a devastating force to be feared and hated, myths and legends are filled with horrors brought about by fire. Any Japanese soldier at the time who operated a flamethrower was automatically awarded the Order of the Golden Kite – the highest military honor possible.

The regular firebombing of Japanese towns and cities by the Allies starting in late 1944 was bringing all these cultural fears to life with traumatizing force. The Japanese decided that the only way to answer fire, was with fire of their own, sent all the way across the ocean through the air.

When our own government found out that these Fugo bombs were actively reaching our shores, they made a choice that had fatal consequences for a few, but also created an unexpected group of heroes. Their decision was to cover up the attacks. In order to understand this choice, we have to talk about America’s attitude towards Japan and Japanese-Americans during the war.

PART TWO

Maybe you’ve never heard of the Battle of Los Angeles, on February 24th and 25th, 1942. It’s not a surprise, it’s one of the most peculiar, and, in a way, embarrassing, battles of World War II. Because it’s a battle in which, to the best of our knowledge, there was never an opponent.

To get here, we need to rewind to Pearl Harbor, which happened just two and a half months before. That surprise attack had shocked America to its core, and unified the population around entering a war we had been avoiding for years. There was a fever of fear and paranoia about where Japan might strike back, not to mention urgent questions about how the attack on Pearl Harbor had happened to begin with.

The Japanese military was on our doorstep. Japanese submarines were attacking, harassing, and even sinking American merchant ships up and down the West Coast. We had long felt secure on our own continent, but suddenly our government had to race to defend thousands of miles of coast, from the Mexican border all the way up to Alaska. Anti-aircraft guns were installed along the shoreline. 500 U.S. Army troops were even stationed in Burbank at the Walt Disney Studios, worried that the global fame of Mickey Mouse might make his home a target.

The initial study by the U.S. Government on the Pearl Harbor attack made a vague reference to people in the Hawaiian Islands transmitting information to Japan before the attack. It didn’t specify whether these unknown agents were of Japanese descent, but with an enormous population of Japanese descendants living and working on the islands, it was left wide open to that interpretation. In truth, a lot of the information was provided by visitors from Japan posing as tourists, not Japanese Americans. But the report didn’t make that clear.

On top of that, many Americans were shaken by what’s become known as the Niihau Incident, when one of the Japanese pilots who attacked Pearl Harbor made an emergency landing on a small island that his commanders had told him was uninhabited. It turned out to have a small population of both native Hawaiians, and Japanese families. The island had no electricity, they didn’t even know that the attack on Pearl Harbor had occurred, and none of the native Hawaiians spoke his language. In a tragic spiral of events, three Japanese citizens of the island tried to help him escape, taking hostages and setting fires to do so. By the time it was over, two people were dead, including the pilot; and the native Hawaiian residents of the island were unnerved at how people they had lived alongside for so many years could turn on them in a matter of hours.

It was in this atmosphere of tension and mistrust that the Battle of Los Angeles was triggered.

One day before, on February 23, 1942, was the first time Japanese ordinance struck the North American continent. Their government wanted to interrupt one of President Roosevelt’s fireside chats to the American people. They had one submarine, the Imperial Navy submarine I-17, in the waters off of Santa Barbara, about 100 miles up the coast from Los Angeles. The sub’s commander was given order to fire at any available targets.

The I-17 wasn’t designed to fire at the land, the only weapon it could use was its deck gun. But Commander Kozo Nishino followed his orders, brought the sub to the surface, and opened fire. They aimed at a storage tank for aviation fuel at an oil facility, but couldn’t hit it. They destroyed a derrick and a pump house, damaged the local pier. A round whistled over the roof of a popular local inn, whose owner called the Sheriff.

The attack lasted only 20 minutes – the damage was minor, and no one was hurt. But in the charged climate after Pearl Harbor, it caused panic up and down the coast. Rumors spread that the attack was a precursor to a land invasion. People fled inland, watching the skies for Japanese planes. As the submarine departed, one eyewitness claimed they saw it turning south – towards Los Angeles.

Other eyewitnesses said they saw lights along the coast, and suggested that there might be spies in the area, sending signals to the submarine. That’s all these were – rumors and guesses in a frightened atmosphere. Rumors, though, can spread like a wildfire.

The next night, in Los Angeles, the chaos began.

U.S. Naval Intelligence, no doubt anxious to avoid another intelligence debacle like the once that preceded Pearl Harbor, circulated a warning that an attack on California was expected sometime in the next 10 hours. Reports flooded in of flares going off around defense plants. Suddenly, radar picked up an unidentified object in the air, 120 miles off the coast. Crews were scrambled to all the area’s anti-aircraft batteries, and ordered to a status of “ready to fire”. A blackout was ordered. Over the next 45 minutes, people all over the area claimed they saw enemy aircraft in the skies; even though the original object being tracked on radar had vanished.

And then, at 3:06am, February 25th, four batteries opened fire, filling the skies over L. A. with anti-aircraft shells. Their firing prompted other batteries to start firing. In the darkness, the shells and drifting smoke clouds were mistaken for yet more enemy aircraft, accelerating the panic. When the shooting finally stopped, over 1,400 rounds had been fired. And they hadn’t hit anything. Moreover, there was no trace of the supposed enemy aircraft. When the Army Air Force did an intensive investigation in the aftermath, they determined that the object which first spurred the U.S. to open fire at 3:06am, was a weather balloon. I’m tempted to say…enough with those darned balloons!

Arguments ran for days about whether we had really been attacked, whether it was a Japanese strategy to reveal our defenses, or create psychological terror. Wendell Willkie, who had run for President against FDR in 1940 and subsequently traveled to London on his behalf to coordinate military aid at the height of the Blitz, was in Los Angeles the day after the supposed battle, and said in a speech that if a real air raid happened, quote: “you won’t have to argue about it—you’ll just know.”

Taken in isolation, we could view the Battle of Los Angeles as a funny blunder. The only known casualty was one local citizen who died of heart failure during the panic. But after Pearl Harbor, Niihau, and the attack on Santa Barbara, a debate which had been raging behind the scenes in the Roosevelt White House was finally resolved, with terrible consequences.

One faction on Roosevelt’s team had been arguing long before Pearl Harbor that Japanese Americans had to be considered potential spies and saboteurs. Roosevelt had experts examining the issue for months, and those experts claimed the opposite, that their studies showed that Americans of Japanese ancestry possessed, quote, “a remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty,” end quote. Tens of thousands of second-generation Japanese-Americans, known as Nisei, volunteered to fight for America in the war, and the 100th Infantry Battalion, a segregated unit made up entirely of Nisei, was the most decorated unit in American military history.

But it was getting more difficult to push back against the aggressive suspicion. The week before the Battle of Los Angeles, the President signed an executive order which allowed regional commanders to designate any part of America a, quote, “military areas”; and then gave them the authority exclude anyone, military or civilian, from these military areas, as the commanders saw fit. This Order didn’t mention the Japanese at all; but it proved one of the most important lessons of history: if you give people power, they will use it.

While all of this was happening, back east, the FBI broke the largest case of espionage in its history. It was known as the Duquesne spy ring, a network of Nazi informants and saboteurs that government agents infiltrated, exposed, and arrested. A total of 33 spies were convicted. Again, those 33 convictions represent the largest espionage case in America’s history.

But on the West Coast, without even one provable case of espionage, the U.S. military rounded up over 120,000 Japanese-American citizens, forced them out of their homes, and placed them in internment camps. Colonel Karl Bendetsen, the architect of the program, said, quote, "I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp." End quote.

As sickening as that sounds, it wasn’t far off from public opinion at that point. The Los Angeles Times, which had previously published editorials defending the local Japanese-American population, now stated, quote, “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched.” End quote.

Interment changed the course of countless lives, and is a lasting stain. It’s also an important reminder that the impulse to declare any class of people unworthy is evil. Even my own family was touched by this tragedy. Masamichi Suzuki was born on October 18, 1918 in Acampo California, near Sacramento where he was raised. After receiving his bachelor’s degree, he started medical school at the Univeristy of California San Francisco. As an American citizen of Japanese descent, Masamichi, or uncle Mac as we called him, was forced to leave medical school in his third year and was placed in an internment camp on June 24, 1942. During his time there, he served as a camp doctor.

At the same time, another Japanese-American Fred Korematsu, resisted being expelled from his home, became a fugitive, and after his capture, worked to challenge the legality of internment all the way to the Supreme Court in December of 1944. Famously, he lost the case, but it helped prompt President Roosevelt to rescind the military’s power to exclude people from their homes.

Uncle Mac was released two years later on the condition that he not live on the US coast during the remainder of the war. He finished his medical degree at Wayne state Medical School in Detroit Michigan then served on the Atomic Bomb Causality Commission that studied the effects of radiation on fertility in Japan. That’s where he met my great aunt, Zoe Green, who was a nurse also working at the commission in Japan. They were married October 6, 1951. Later he served as the chief OBGYN at Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas before being honorably discharged as a Major. A practicing OBGYN in Michigan, his work blessed the lives of thousands of families. He passed away on December 19, 2014. On the same trip where I visited Thermopolis, I visited the grave site of Mac and Zoe Suzuki, whose mortal remains rest in the shadows of the Teton mountains.

Examples of countless loyal Americans like Mac Suzuki and the Korematsu case made America confront how wrong it was to punish and dehumanize innocent civilians based only on their ancestry. And FDR had some sense of how weary America was of war, and how dangerous a new round of panic could be. I think this dynamic helps explain why, when Japan made its last, and strangest, attempt to strike at our mainland, our government decided to cover it up.

PART THREE

The Fu-Go Balloon was a simple, ingenious, and frightening device. It was 33 feet in diameter and could lift approximately 1,000 pounds. An unpiloted hot air balloon, it was wired with an altimeter to stay between 30,000 and 38,000 feet, where the jet stream described by Wasaburo Oishi would propel it all the way across the Pacific Ocean. Powered only by the wind, it could travel from the coast of Japan to the coast of America in just three days. After that time, a fuse would light automatically, and the balloon would drop 33 pound incendiary bombs made of thermite. Each bomb had a 64 foot long fuse that would burn for 82 minutes before detonating. While the bombs were anti-personnel explosives, the strategic idea was not to randomly kill a couple of civilians, but to start massive wildfires in America’s western forests, spreading panic and death, and diverting America’s attention and resources.

Japan had a history of using unconventional weaponry. During their war with China prior to World War II, they had unleashed a horrifying array of biological weapons. In 1942, they even developed a plan to drop 200 pounds of plague-infested fleas on American troops in the Philippines. The operation was only canceled because the Americans surrendered beforehand. They had a large stock of bioweapons available even in late 1944, but the order to use firebombs came from the Emperor himself. They knew the balloons would have a high failure rate and mostly land in unpopulated areas, so they didn’t want their bioweapons to go to waste. And fire fit the mission of vengeance for the infernos which were consuming Japanese towns.

The first Fu-Go balloon bombs were launched on November 3, 1944. The military went into mass production on these inexpensive weapons; setting up makeshift production centers in any spacious buildings they could find – even theatres and sumo halls. Many of the workers were schoolgirls, conscripted to contribute to the war effort. But they faced an obstacle that, to me, underlines what a dire state the population of Japan was in after so many years of being asked to sacrifice for their Emperor. The envelope of each balloon was held together by a special paste called konnyaku, made from an Asian plant similar to a potato. The paste was edible, and the workers were often so starved and desperate, they were smuggling out the paste to eat.

Eventually, over 9,000 Fu-Go balloons were launched towards the United States. They spread all over the North American continent, as far north as Alaska and the Yukon territory, as far east as Michigan. So why is this rarely talked about in history? One reason is that the war didn’t last long enough for this experimental weapon to overcome several obstacles, which we’ll talk about. The other is that a group of American heroes put their lives on the line in order to help keep this campaign of bombardment a secret. This group of heroes was the U.S. Army 555th Parachute Battalion – the Triple Nickels.

In late 1943, a group of paratroopers from the 92nd Infantry Division was hand-selected for an experimental new unit. Paratroopers are the elite, and these were the elite of the elite – from the commanding officer to the lowest-ranking private, they were the soldiers rated as the most exceptional in physical fitness and intelligence. Hardened combat veterans were placed alongside world-class athletes and college professors. Created when the US military was segregated by race, the 555th was the only African American parachute unit. They were all Black, the first combat unit of all Black Americans, commanded by Black Officers, assembled in the U.S. Army since the Civil War. Black Civil War Cavalry Regiments were nicknamed Buffalo Soldiers. This new unit, the 555th, decided that the fives in their name represented Buffalo Nickels. Hence – the Triple Nickels.

The Triple Nickels started training at Ft. Benning, Georgia, deep in the south. Segregation affected every part of their life and training. While there was a limited amount of solidarity with their white comrades on base training, working and eating together; off base they continued to encounter discrimination, segregation and police abuse.

Then there was the question of where this special unit was to be deployed. The company transferred to Camp Mackall in North Carolina in July 1944 to train for duty in Europe as their initial orders had them preparing to air drop into Germany. But there was debate within the Army that if this all-elite fighting unit distinguished themselves in combat, it could hurt the morale of units filled by white soldiers. Black soldiers were constantly slandered as cowardly, as unreliable. The 555th was poised to prove that argument wrong. But they never got the chance. With the Nazi military in collapse, the government ordered them to a most unexpected place – Pendleton, Oregon. The Triple Nickels were assigned to work for the U.S. Forest Service. But this wasn’t a ticket out of danger – quite the opposite.

Forest fires are a nightmare to try and contain. They can start many miles from any people, and they’re a natural part of the life cycle of a forest, but they can quickly become a lethal threat if they suddenly leap towards civilization. And if you need to deploy firefighters swiftly to a remote spot in a the woods, you have to drop them in as it’s nearly impossible to move people and equipment quickly through a thick forest. This is called smokejumping – parachuting out of an aircraft, and into a raging inferno. And the pioneers in this astounding, unimaginably dangerous work, were the 555th Parachute Battalion. The original smokejumpers.

The government had spotted some of the very first wave of Fu-Go balloons, and in a matter of weeks had guessed at what their intent was. The government thought it might be better to try and prevent a second wave of panic and xenophobia, especially over a weapon that didn’t seem to be very effective yet. So, they kept their discovery of these balloons quiet. The Office of Censorship – yes, we had one – asked newspapers and radio stations to not report on stories about balloons. When civilians like farmers and ranchers would discover balloons on their property, government officials would tell a cover story, pretending they were weather balloons. This practice must have paid off by the time that balloon crashed in Roswell, New Mexico – listen to our episode about the Val Johnson UFO encounter for more on that.

But the key to keeping a lid on this story was making sure that the balloons didn’t succeed in starting any large-scale forest fires. So the Triple Nickels were there to bring the firefighting efforts of the U.S. Forest Service into the modern world, and go after any forest fires in the Pacific Northwest, whether the cause was enemy action, or just Mother Nature. Their mission was known as “The Firefly Project”, and they were ready to deploy anywhere from California to Montana.

To become a smokejumper is to unlearn everything you’ve learned about parachuting. A trained paratrooper from the 555th would always be seeking even, open ground to land in. But in a forest fire, this isn’t possible; a smokejumper is trained to land in a tree, get free of their parachute, and then lower themselves to the ground with a nylon rope. To make matters worse, no specialized equipment existed for this seemingly insane work – the Triple Nickels leapt into danger wearing asbestos suits over their regular gear, with a modified football helmet on top.

And, on top of this incredibly dangerous training just to teach them to reach the location, the soldiers of the 555th then needed to learn how to fight forest fires. But remember, these were the best of the best, and in the high-pressure environment of the segregated South, they’d learned to rely on each other.

The firefighting record of the Triple Nickels is extraordinary. They were deployed to 36 fires around the Western United States, completing over 1,200 jumps in the process; laying the groundwork for every smokejumping crew that followed in their wake.

On August 6th, 1945, the Triple Nickels were called to the Umpqua National Forest outside Lemon Butte, Montana. 15 of them were set to deploy into the fire; but their assigned medic reported ill at the last minute. Private First Class Malvin Brown, a fellow combat medic in the Battalion, volunteered to take his place. Private Brown, originally from Pennsylvania, had volunteered every step of the way, starting when he volunteered for the Army in 1942. After he had been identified as a young man with exceptional intelligence and promise, he volunteered to join the high-risk 555th Battalion; taking on not only their punishing training regimen, but an extra three months of intensive study and field work for his position as a combat medic.

When the Triple Nickels jumped, they were caught up in a harsh wind, which blew them away from their landing zone into a thicker part of the forest. Private Brown found a tree to land in, according to plan; but then, a sudden accident. He fell from the tree, landing head-first in a ravine, 150 feet below. The impact killed him instantly.

His fellow jumpers were not going to leave him behind for the fire. They pulled his body over 1,000 feet up an 80% slope, then walked with him all day and night, fifteen miles through back country and trails, so his remains could be sent home to Pennsylvania.

In over 1,200 jumps, performing an unimaginably dangerous job that they were inventing as they went along, the Triple Nickels only suffered one fatality, Private First Class Malvin Brown. The area where he died has been commemorated with a plaque, and is known as “Fireman’s Leap”. Their secret mission had succeeded; and most Americans, to this day, don’t even know about the invasion of the Fu-Go Balloons.

If the date of Malvin Brown’s death, August 6th, 1945, sounds familiar, it’s the same day that the American B29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. The war of air and fire was coming to an end.

PART FOUR

Remember that phrase from the beginning of the episode, the one in Esperanto? “To Our Good and Loyal Subjects?” Those were the first words spoken in what’s become known as the Jewel Voice Broadcast, a radio address by Emperor Hirohito to the citizens of Japan, proclaiming their surrender to the Allies one month after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Japanese people had believed their Emperor was more than human, closer to a God. No ordinary citizen had ever heard his voice before. To add to the shock and confusion, the Emperor spoke in Classical Japanese, which was too arcane for most of his own subjects to understand. After the speech, news broadcasters had to confirm that yes, this was the voice of the Emperor, and it was saying the War was coming to an end.

I can’t help but think about the coincidence of the Emperor, disconnected by his language and his immense power from the subjects who had sacrificed so many lives to him, and Wasaburo Oishi, who had published his discovery of the jet stream in Esperanto because of how deeply he believed in connecting humanity through language, and through science.

Of the more than 9,000 Fu-Go Balloons deployed to attack America, it’s believed that less than 10% of them ever successfully reached us.

On December 6, 1944, the first known sighting occurred in Gebo, a small mining town near Thermopolis Wyoming. At 6:15pm, three men and a woman heard a soft whistling overhead, followed by an explosion. Looking up, they saw flames in the sky and something like a parachute floating down. Later the balloon was found. At the time, Gebo was a town of several hundred people as coal mining in the area started in the late 1880s when the Jones Mine opened in the summer of 1889.

When you see the terrain of this part of Wyoming, you realize that there just wasn’t a lot to burn. Other than tall grass, there are few trees and scrawny bushes. So when Fugo balloons landed in locations like this, the risk of fire was almost zero. Also, the jet stream was at its strongest in the winter months, so if a balloon did happen to reach a thick forest, it was likely to be cold and damp, and far less likely to burn.

By the spring of 1945, the risk was largely over. Bombing raids had destroyed two of the three hydrogen plants used to fuel the balloons. And unbeknownst to America, the Japanese abandoned the idea as a failure they could no longer afford, sending their last balloons in April of 1945, four months before the fatal smokejump of Private Brown.

But still, there were casualties. In May of 1945, Pastor Archie Mitchell, his pregnant wife Elsie, and five students from their Sunday school, were picnicking in the woods near Bly, Oregon. They discovered an old, downed balloon on the ground, whose fuse had failed to ignite. Since the government had covered up stories about these devices, this group didn’t know how dangerous it was. They accidentally triggered the bombs on-board, killing Elsie and the five children. They are the only known casualties of the entire Fu-Go balloon campaign.

And Gebo? At the time of the 1900 census, the town hadn’t existed and by 1938, mining had largely ended. When you visit the website, you can see two incredible photos – one of Gebo with scores of homes and buildings when the town reached its peak in 1923 – and one as it sits today, the area almost returned to its natural state except for the stone shells of a handful of homes. Almost like the story of the Fu-go balloons themselves, this town faded into history.

There’s an amazing connection between people and events of this unique period of history. Like the use of the jet stream to deliver the explosive Fugo balloons, sometimes that connection has an unfortunate start. Yet as we follow these connections, we meet individuals who can inspire us – like Dr. Mac Suzuki, Fred Korematsu, Private Malvin Brown. All of whom answered the call and found a way to be heroes for a country who didn’t know heroes could look like them. As Martin Luther King said: "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Mac, Fred & Malvin lived in ways that lit this sad, dark path of history.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host. Thank yous to Nicholas Thurkettle, the lead writer on this episode and our editor, Alex Bagosy, our lead researcher, Emily Wolf, our producer and Dom Purdie our sound engineer.

If you like My Dark Path, please take a moment today to help us reach new listeners. You can do this by reviewing this episode and sharing it with a friend or family member. And remember, if you want one of these limited edition My Dark Path t-shirts, just send me an email at explore@mydarkpath.com with your review or story idea. We only have about 30 left.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me, your host, MF Thomas. Until next time, good night.

Listen to learn more about

The earliest scientific discovery of the jet stream.

The anxiety of the American population in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Niihau Incident, and the I-17 submarine attack on Santa Barbara.

The Battle of Los Angeles.

The origins of the camps where the US government interned Japanese-Americans.

The Japanese Fu-go strategy and why the US government kept this audacious attack secret at the end of the war.

The origins of the U.S. Army 555th Parachute Battalion, the Triple Nickels.

The Firefly Project, where the Triple Nickels became the first smoke jumpers, suppressing the fires caused by the Fu-go balloons.

References

Universala Esperanto-Asocio, Universal Esperanto Association.

“The Jewel Voice Broadcast.” Atomic Heritage Foundation, Atomic Heritage Foundation.

Weeks, Linton. “Beware of Japanese Balloon Bombs.” NPR History Dept. NPR.

Music

Undaunted, Alice in Winter

Brenner, Falls

Genesis, Alice in Winter

System 6, Fairlight

Hold This Place, Alice in Winter

Slow & Steady, Fairlight

Together, Kevin Graham

Unfolding, Alice in Winter

Perfect Spades, Third Age, Nu Alkemi$t