Episode 17: The Lost Olympics of 1906

How could an entire international competition involving dozens of nations and hundreds of elite athletes be stricken from the official history of the Olympic Games? We love the Olympics here on this podcast, which is why we’re devoting two episodes in a row to them as the Tokyo Games are unfolding; but in order to solve this mystery of the Lost Olympics of 1906, we’re going to have to walk a dark path of politics and history. It will be worth it to celebrate the real achievements of people like Billy Sherring, and an event whose breakthroughs and innovations still shape the world’s greatest athletic contest today.

Listen To Learn More About:

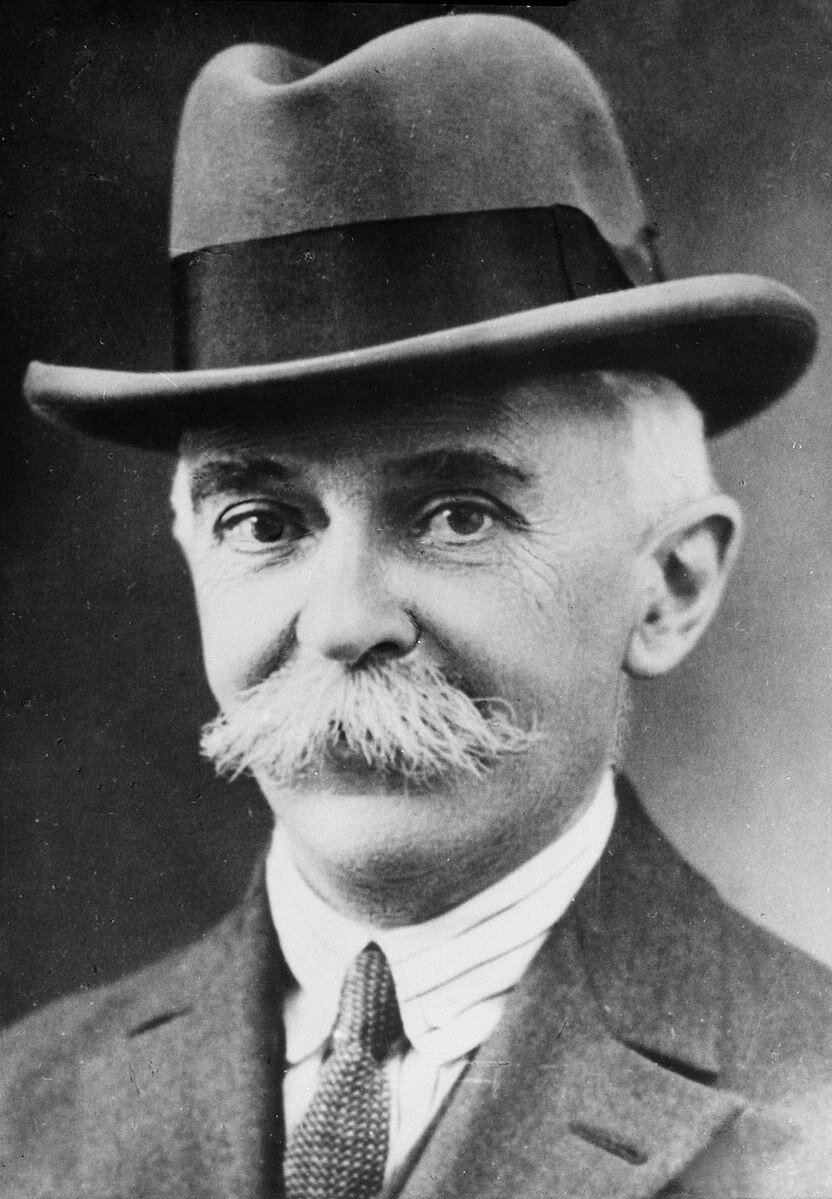

The founding of the IOC and Pierre de Coubertin

The “unofficial” Olympic games of 1906

The gold medalist who was borne with Polio and other amateur Olympians

Athens’ fight to permanently host the Olympics

Billy Sherring

Evaggelos Zappas Statue in Athens

First Nordic Games (1901) Poster Featuring Telemark

Grecian Stadium

Image taken from the 1901 Nordik Olympics Rule Book

Painting Le Départ – in which a young Pierre de Coubertin is depicted, painted by his father Charles

Prince George of Greece in 1902, High Commissioner in Crete

Prince George of Greece in 1902, High Commissioner in Crete

Ray Ewry during standing high jump in the 1904 Summer Olympics

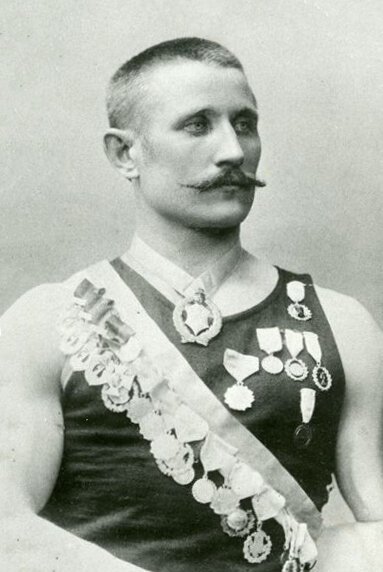

Verner Järvinen

Athens Stadium

Greece

Pierre de Coubertin Anefo

Sources:

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING/MEDIA:

SR Olympic Sports

Why were the ancient Olympics Revived

The Second International Olympic Games in Athens

International Olympics Committee

BBC

Olympedia

Olympics Archive

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

MUSIC:

We Could Begin Again by Cloud Wave

Perfect Spades by Third Age, Nu Alkemi$t

IMAGES:

Statue of Evangelos Zappas, By Badseed on Wikimedia commons:

Full Script

Picture yourself running, under the brilliant Mediterranean sun. You’ve been running for a long time and your muscles are aching, but as you get closer and closer to your destination, adrenaline surges through you and you don’t feel any pain. Just triumph and excitement.

You look around, and your surroundings are gleaming. Shining white marble is everywhere, along with thousands of cheering spectators.

You’re in Athens, Greece, and you are about to win the Olympic marathon. After 26 miles running along Greek roads, you’re in the historic Panathenaic Stadium, which was originally built over 2,000 years ago. You feel the spirits of ancient athletes running alongside you as you take the final lap towards victory. Then you look over, and someone else actually is running alongside you. It’s Prince George of Greece, the son of the King, accompanying you for the final 50 meters.

You cross the finish line, victorious, over 7 minutes ahead of your nearest competitor. All your months of training and sacrifice have paid off. In addition to a medal and a laurel crown, you’re awarded a statue of the goddess Athena, and a live lamb. Your home country names two townships in your honor.

It is greater than any high you could have ever dreamed of experiencing. This, you decide, will be the end of your running career. How could it possibly get better?

Now imagine, finding out later that the International Olympic Committee has ruled that you are no longer an Olympic Champion, and that your medal is no longer an Olympic medal. Not because you did anything wrong, you followed all the rules in running the incredible race you ran. It’s just that the IOC has declared that the Olympics you competed in, no longer count as Olympics.

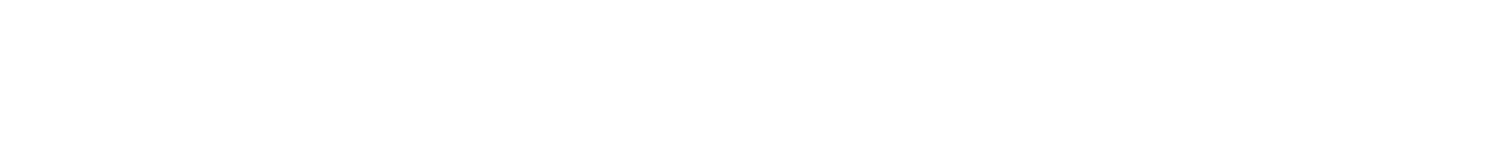

This actually happened, to a Canadian runner named Billy Sherring. In his home province of Ontario, the townships of Sherring and Marathon were named in his honor. He was the champion of the Athens Olympics in 1906. Not the 1896 Games which everyone remembers as launching the modern Olympic movement. But another set of Games in Athens, outside the traditional four-year span between competitions.

For every athlete at those Games, the competition was real, as were the intense feelings of victory or defeat. They were told they were competing in Olympic events. How could an entire international competition involving dozens of nations and hundreds of elite athletes be stricken from the official history of the Olympic Games? We love the Olympics here on this podcast, which is why we’re devoting two episodes in a row to them as the Tokyo Games are unfolding; but in order to solve this mystery of the Lost Olympics of 1906, we’re going to have to walk a dark path of politics and history. It will be worth it, though, to celebrate the real achievements of people like Billy Sherring, and an event whose breakthroughs and innovations still shape the world’s greatest athletic contest today.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 17: The Lost Olympics of 1906.

PART ONE

The story of the modern Olympic Games always begins with Charles Pierre de Frédy, also known as His Excellency Baron Pierre de Coubertin. De Coubertin was born into an aristocratic family that prized a well-rounded, Renaissance education. His father, Baron Charles Louis de Fredy, was an accomplished painter, and a five-year-old Pierre actually appears in one of his works, Le Départ, which is still on display at the Chapel of the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

His parents didn’t let him rest on his privilege. He received a rigorous upbringing at a strict Jesuit boarding school, and de Coubertin always believed that the combination of humility and boundaries helped build his character.

He grew up in an atmosphere of instability and international embarrassment for France. The defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and -71, the collapse of the Empire of Napoleon the III, massive losses of territory, reparations, and a long debate over whether or not to restore the French monarchy, saw his nation at a crossroads, questioning its identity and its values. The young Pierre found himself wondering what could be done to restore pride and character to his country.

He fell in love with the English style of education, which included athletic development and team sport, valuing the development of the body as well as the mind. He believed that the expanding dominance of the British Empire could be credited to the, quote, “moral and social strength,” its young men developed through sport. He saw a parallel between British schooling and the Ancient Greek gymnasium – which in those times not only was a place for athletes to train, but to socialize and study.

Needless to say, there is a lot more to the history of empires than whether or not their citizens played sports in school, but it set de Coubertin on the path to leading a revival of the Olympic Games. And here we have to depart from the official narrative generally promoted by the International Olympic Committee, the organization he co-founded which produces the Olympics to this day. Because he wasn’t the first person to propose reviving the ancient tradition, he wasn’t even the first person to do it. In England in the early 1600’s, King James I approved a public sporting event known as the Cotswold Olimpicks – some of the events included hunting with hounds, chess, dancing, sword fighting, and sledgehammer throwing. Amazingly, a descendent of this event still happens every year at Chipping Camden in Gloucestershire, though it’s no longer anything like a serious athletic pursuit. If you ever go, you’ll see a lot of drinking going on, along with “events” such as shin-kicking, piano smashing, and “dwile flonking”, which I’ll let you look up on your own.

In 1850 another British competition was launched, known as the Wenlock Olympic Games. This one was taken a bit more seriously, and Baron de Coubertin even attended these Games and consulted with its founder. Meanwhile, in Greece, a wealthy philanthropist named Evangelis Zappas (“ZAH-Pas”). funded the restoration of the 2,000-year-old Panathenaic Stadium, and produced two international competitions there in 1870 and 1875. They’re now affectionately called the Zappas Olympics, and they drew tens of thousands of fans to see athletes from around the Ottoman Empire. And Zappas’s legacy with the Olympics runs even deeper; he established a trust fund which the city of Athens used to help finance the 1896 Games.

Part of the appeal of the Games was the self-improvement concept; and the desire to find a link between one’s culture and the cradle of Western Civilization. But the Olympics also attracted interest because it was known that wars in Ancient Greece were put on hold whenever the Games were held. These Olympic truces didn’t always work; but since the continent of Europe in the 19th century had been consumed by a seemingly endless series of wars between would-be empires, the hope of creating a cause that might compel a break in all the fighting would have been attractive indeed.

Even though it seems obvious in retrospect that the Olympics would be revived where it all began, in Athens, this wasn’t at all a guaranteed outcome. When Baron de Coubertin founded the IOC, he gathered representatives from the sports communities in 11 nations at the Sorbonne in Paris. This was 1894, and he suggested holding the games in Paris in 1900. A World’s Fair known as the Universal Exposition was scheduled to be held there to usher in the 20th Century, and with the eyes of the world already on Paris, de Coubertin believed this would be the ideal moment to launch his international spectacle. Already he envisioned that the Olympics would move around the world, appearing in a different major city every four years.

But there was concern that, if the event wasn’t going to happen for six years, the organizers might lose resources and momentum. We don’t know who proposed the idea first, but by the end of the Paris meeting, it was decided that the first modern Games would happen in Athens in 1896. They already had the legacy; and thanks to Evangelis Zappas, they had the main facility, and the money.

It’s impossible to overstate what a logistical and political triumph it was, in less than two years, to get 241 athletes from 14 nations to come to Athens to compete. So many European countries had fresh and furious memories of war with one another. French athletes didn’t want to compete with German athletes; German athletes heard rumors that they would be barred from competing until Baron de Coubertin wrote a personal letter to the Kaiser assuring him this wasn’t so. King George of Greece wanted to be seen as founder, host, and mastermind of the whole spectacle, and he had powerful family ties to the rulers of Great Britain and Russia. He and de Coubertin were barely on speaking terms by the time the Games opened.

And yet, after 10 days of competition, the 1896 Modern Olympic Games were an enormous success. In a way, this success is what led to the next dispute. Because Athens enjoyed these new Olympics so much, they wanted to keep them.

A large contingent began to advocate for Athens to be the permanent home of the Games. King George himself encouraged it, and laws were passed that would encourage the development necessary to make it happen. Many of the athletes who had competed in the Games, including nearly all the Americans, made public pronouncements in support.

Baron de Coubertin never publicly wavered in his belief that the Olympics should belong to the whole world – guaranteeing an Olympic Games in Paris in the year 1900 had helped cement the delicate and complex series of deals that helped revive them in the first place. And now that the Games were considered a success, there were plenty of people stepping up to take the credit, and de Coubertin no longer had total control over the IOC. Internal politicking became more intense; there’s even evidence that he changed the locations of Committee meetings in order to ensure that a majority of people in attendance would be those who supported him.

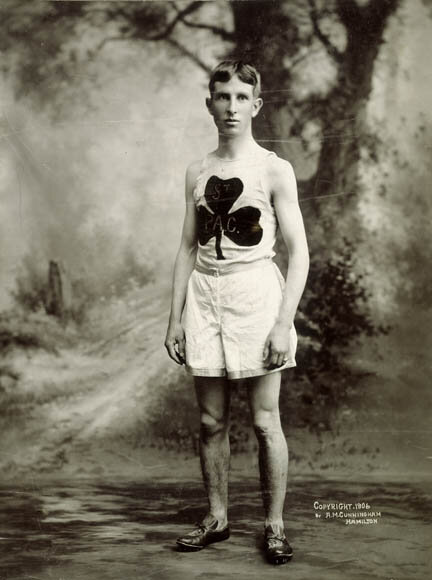

The record shows that he wasn’t opposed to Olympic Competitions happening outside the four-year cycle. In 1901, a member of the IOC created an athletic contest called the Nordic Games. Think of them as like a precursor to the Winter Olympics – they happened 8 times between 1901 and 1925, and featured cold-weather events – skiing, skating, hockey, curling, and more. Although they didn’t have the full participation of the IOC, and the athletes were almost entirely from Nordic countries, de Coubertin publicly acknowledged and praised them, even called them the “Nordic Olympics”.

Digging into various memos, journals, and readouts of IOC meetings and events, it appears as though the status of the 1906 Games, and the possibility of continued events in Athens, had become a proxy for a power struggle over control of the IOC itself, with the Baron fighting in the face of the growing international popularity of the Games to keep it tied to his personal vision of what they should be.

But the proposal wouldn’t go away. The 1900 Games in Paris were largely viewed as a disappointment – scattered across months, with a glut of odd and unappealing events, some of which we described in our previous episode. Rather than gain attention from Paris’s Universal Exposition, they were completely overshadowed by it – the Olympics were a sideshow.

The idea of an alternate games in Athens was proposed again at an IOC Session in Paris, this time by the German delegation. It’s speculated that the Germans were the ones that de Coubertin was trying to keep out of previous meetings by moving the location around at the last minute; the German government had an interest in gaining influence with Greece, and advocating for the Olympics they badly wanted would have been a useful way to gain favor.

And this time, despite de Coubertin’s disapproval, the International Olympic Committee voted to award Athens an Olympic Games, to be held in-between the four-year cycle of the traveling Games. In a letter, de Coubertin referred to them as “Panhellenic Games”. Other proposals referred to them as the “Athenaia” – Greek-centered contests that international athletes would nonetheless be invited to. But Athens intended to make a full, international spectacle out of it.

Making them happen by 1902 was out of the question, though. After the triumphant 1896 Games, Greece had been engulfed in a swift but incredibly costly war with the Ottoman Empire over the island of Crete. Their economy was severely constrained, their national pride in tatters. Instead, planning for a new Games moved to the next year in their cycle, 1906.

To whatever extent Baron de Coubertin offered support, it was in a passive way, you might describe his attitude as, “we won’t stop you from doing it”. He took the public position that the IOC had no responsibilities with regards to the planning or execution of the Games; the responsibility lay with the host city. In his words, quote:

“For the year 1906 Games have been announced in Greece which do not belong in the proper order. It was agreed that the I.O.C. would lend its support, as well as the already existing organisations in various countries”.

End quote. Hardly the words of an enthusiastic booster.

Meanwhile, the 1904 Olympics were an absolute disaster. The Games had originally been scheduled for Chicago, but down in St. Louis, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was going to happen at the same time; and they threatened to hold their own international sporting events if Chicago hosted the Olympics. De Coubertin caved, and awarded the Games to St. Louis. He watched as another Olympics got overshadowed by a World’s Fair. Meanwhile, the Russo-Japanese War prevented many of the world’s top athletes from traveling to America to compete, and events were scattered across almost five months. Some of them doubled as the official U.S. Championships, so a few athletes weren’t even aware they were competing in the Olympics.

Most embarrassing of all in the eyes of history, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition organizers mixed in contests they called “Anthropology Days”, in which indigenous men from Africa, Asia, and First Nations tribes were pitted against international athletes in track and field events. With no training or experience, they naturally lost these contests, which was held up as proof of the superiority of athletes from quote-unquote “civilized” nations. The local media referred to it as the “Savage Olympics”, a disgusting spectacle which unfortunately reflected cultural attitudes that were all too common at the time.

Whatever Pierre de Coubertin had originally imagined for his Olympic dream, it was in danger of dying. The 1908 Games had been awarded to Rome, but in early 1906, the Italian volcano Mt. Vesuvius erupted, a devastating national catastrophe which ruined preparations that were already far behind schedule. With the IOC scrambling to find an alternate host, their attention wasn’t focused on what Athens was doing. But the 1906 Games were real, and ready to welcome the world.

Following the IOC’s rules, Baron de Coubertin published the program for the event in the Revue Olympique. But he didn’t list the exact dates, and left out information on how athletes could register for participation, which seems passive-aggressive, to say the least. He does, however, refer to them in print as “the Olympic Games of 1906”; so any claim after the fact that these were never intended to be considered official Olympics stands on the shakiest ground.

True to his word, Athens had been left alone to plan how their Games would work. And it turns out, the ideas they came up with revolutionized the modern Olympics. And, in our opinion, saved them.

PART TWO

Remember Billy Sherring, the Canadian marathon runner I told you about in the opening? His story is even more inspiring than what I shared. He worked as a railway brakeman, an incredibly dangerous job that required running along the top of a moving train and operating wheels and cranks while the train was taking steep turns or sharp drops. Casualties were rampant; but Billy Sherring had survived, and despite his humble career he was known as one of the best amateur distance runners in the world.

When news of the Athens 1906 Games reached him, it was a real question whether or not he could make it across the ocean to compete. Although it’s hard to verify, the story goes that between his own meager earnings and some support from the community, he was able to raise about 90 dollars; but this wasn’t nearly enough. On a tip from a bartender, though, he bet the entire 90 dollars on a horse race. His horse came in, paying six to one – and now he had his travel funds.

He traveled to Athens two months early, and took a job as a porter at the local rail station to support himself while he trained in the intense Mediterranean heat. By some accounts, he lost twenty pounds in just seven weeks as he got used to the local conditions. What’s even stranger – he may have been one of the only athletes doing this, and it’s undoubtedly part of the reason why he was seven minutes ahead of everyone else in the field when he won the race.

As we discussed in our last episode, the definition of “amateur” competitor has always been a hazy one in the history of the Olympics. Baron de Coubertin might have imagined a friendly sporting contest between well-rounded Renaissance gentlemen, but the human race is a little more specialized than that; and Olympic athletes nearly always had the benefit of some institutional training – whether it was the military, law enforcement, or even just a job that developed their muscles in the right way. But the idea of advance training was considered questionable, even possibly uncouth.

Nevertheless, the level of competition in 1906 was a giant leap ahead of the prior Olympics. The IOC had established a global network of organizations called NOC’s – National Olympic Committees. Now, if an athlete wanted to compete representing their country, they had to be qualified by their country’s NOC. With national pride on the line, the NOC’s set standards for who could compete, and with this one change, the 1906 Games featured one of the greatest collections of International athletes ever seen to that point.

They also did away with the idea of competing for attention with a World’s Fair, or spreading the Games across multiple months. As with the 1896 Games in Athens, these competitions happened in a focused, intense period – with everyone’s attention riveted by 11 straight days of the highest-quality sport.

For the first time in history, there was a dedicated facility for athletes and their trainers to live during the Games. Living conditions at the first-ever Olympic Village were apparently pretty dire – there’s a reference to the foreign athletes finding Greek food to be, quote, “strange”. Nevertheless, this is another tradition which has carried on at every Olympic Games since.

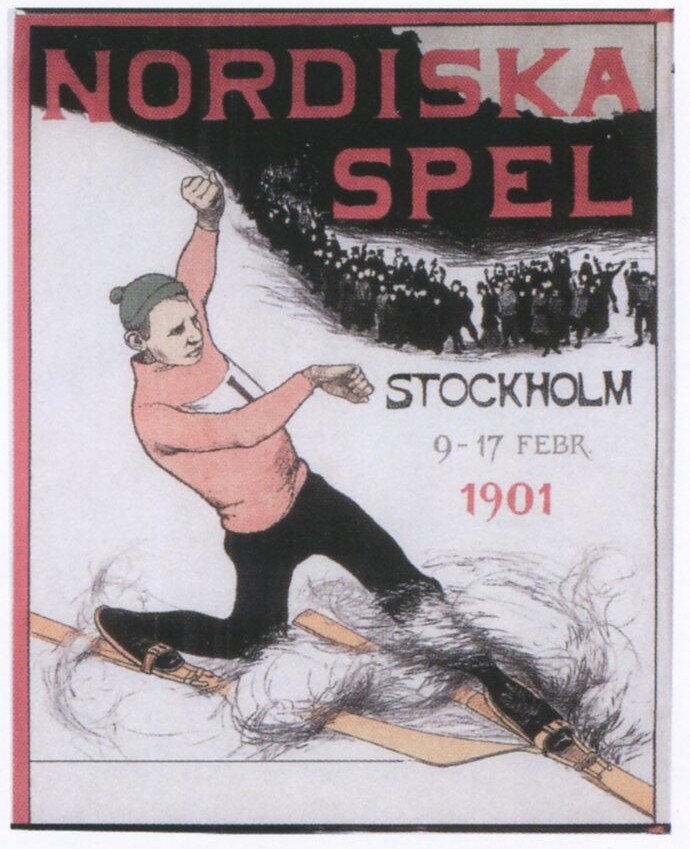

This was the first Olympic Games to open with a parade of the athletes, marching around the stadium behind their respective national flags. The Greek athletes marched in last, a tradition that is still honored today. King George of Greece presided over the spectacle, with a very special guest – King Edward VII of England. He was King George’s brother-in-law.

The Games also featured what’s believed to be the first-ever Olympic Closing Ceremonies, where every athlete was presented with a medal for participating. Think about how inseparable these bookends have become to the celebration of the Games, how many unforgettable moments have happened during the Opening and Closing Ceremonies. The more you learn about the 1906 Games, the more astonishing it is to think of them as anything but real Olympics.

Now, they were far from perfect in the execution. A lot of rules and procedures weren’t fully-formalized yet. The track at the stadium wasn’t even regulation length; plus its surface was soft, and runners were made to travel around it clockwise, instead of the counter-clockwise path that’s standard nearly everywhere else. Meanwhile, the diving events were actually held outdoors, on a special platform built on top of a boat placed in Neo Phaliron Bay, where high winds and bad weather caused constant delays and difficulties for the competitors.

In addition to these venue-related challenges, nearly all the event judges were Greek, and therefore vulnerable to accusations of favoritism towards local competitors. Future Games would make sure that the judges always represented a wide range of nationalities.

But despite all these challenges, these Games provided its share of dramatic moments and astounding feats. An American named Ray Ewry won gold in both the standing long jump and the standing high jump. As if that wasn’t impressive enough, he had already won three gold medals in jumping events in both 1904 AND 1900. And before I forget to mention – Ray Ewry spent much of his childhood in a wheelchair because of polio. His unbelievable leg strength was developed as he exercised to overcome his condition.

He won the same two gold medals in the 1908 Games, and having 10 Gold medals would make him the second greatest Olympic Gold Medalist in history, trailing only the legendary swimmer Michael Phelps. But, since the IOC declared that his 1906 Gold medals don’t count as Olympic medals, his official tally is eight golds in eight events, tying him with the sprinter Usain Bolt. Hard to feel sorry for him, really.

Or consider Venne Järvinen the first athlete from Finland to compete in the Games. A former wrestler with extraordinary upper body strength, Järvinen competed in Athens in the shot put, the javelin, the discus, and the Greek-style discus. He won bronze in discus and gold in Greek-style discus. He even had the longest distance in the shot put, but was disqualified – the judges ruled that he had thrown the shot, rather than “put” it.

With the IOC’s ruling, Finland’s first-ever Olympic Gold was erased from history. This is an even more egregious insult when you consider that Finland at the time was part of the Russian Empire; it was a special privilege that the IOC had recognized Finland as a separate nation for the sake of the competition; otherwise Järvinen’s medals would have been credited to Russia. Järvinen returned for the 1908 Olympic Games, but won only a bronze in Greek-style discus. Later, he trained three of his four sons to become Olympic athletes themselves – and his son Aki set the world record in the decathlon. There’s a family a whole nation could root for.

Peter O'Connor won gold in the hop, step and jump, now known as the triple jump, as well as silver in the long jump. He was born in Ireland but, officially, competing under the British flag. If you know anything about the history between Great Britain and Ireland, especially in the early 20th century, you won’t be surprised when I tell you he wasn’t happy about winning a medal for the British. In an act of protest, he actually scaled the stadium flagpole and hoisted an Irish flag. Irish and Irish-American athletes helped to guard the pole while he climbed.

The French tennis master Max Decugis won the gold in all three of the events he entered, including the mixed doubles contest – his partner was his wife Marie. A legendary French marksman named Léon Moreaux won five medals, including in one of those dueling events we mentioned in our last episode. Moreaux was 54 years old, one of the oldest competitors in Olympic history. He competed again at age 56 in the London Olympics and, even more incredibly, at age 62, he enlisted for military service in the Great War, survived the battlefield, and was appointed to the Legion of Honor.

All these achievements, these stories, these astonishing people from the world of sport, are disavowed by the International Olympic Committee. Witnesses have even reported that in the official Olympic Museum, there are photographs of events from the 1906 Athens Games, but with false captions, claiming they’re from the 1896 Athens Olympics. How did this happen?

PART THREE

After the 1906 Games, Baron de Coubertin found himself fighting to remain the head of the IOC. There was an attempt to maneuver around his presidency and establish a new ruling committee, with the honorary chairmanship to be given to the Crown Prince of Greece. Although there’s nothing concrete in the historical record, there are some hints in references to various meetings and letters that he found powerful allies in Great Britain who helped protect his Presidency. This would have been right around the time that the 1908 Olympics were suddenly moved from Rome to London. For this reason, he might have come to see any reference to Greece as part of an existential threat to his authority, not to mention his vision for the Games.

But even as he clung to power, Greece was serious about continuing to hold an Olympics in Athens every four years. Extensive planning took place to hold another in 1910. American President Theodore Roosevelt would have been named the honorary President of the Games. Work continued right up to the fall of 1909, but escalating costs and military unrest throughout the region forced the organizers to cancel. A smaller, four-day event was held in April of 1910, and was dubbed the Panhellenic Games.

Turmoil continued to engulf the nation, including the outbreak of two wars in the Balkans, and the assassination of King George. The King enjoyed great popularity among Greek citizens, and often walked without a security detail; a mistake that proved fatal. All it took was one activist with a gun. Greece was sitting right on one of the political fault lines that was destined to fracture in just a few years with the outbreak of the first World War.

Some planning was attempted for a 1914 Athens Olympics – a preliminary program was published and there’s a reference in it to “balloon and aeroplane competitions.” That would have thrilled my whole team over here; but by 1914, the Great War had turned the entire continent of Europe into a killing field. Baron de Coubertin’s grand vision of the Games as an event which could bring about peace was brutally rebuked by history. The 1916 Games, which had been scheduled for Berlin, were canceled.

Athens didn’t make another proposal to host for many years. The Games of 1976, 1980, and 1984 were all rocked by large-scale boycotts against their host countries, robbing them of the promise of pitting the world’s greatest athletes against one another. During this time, a small movement proposed that Athens could serve as a kind of neutral ground, a place whose right to host the Games couldn’t be questioned by anyone. But this movement never got very far – by this point the IOC had immense power and resources, selling the TV rights to the Games now brought them an explosion of wealth every four years. No country wanted to stick its neck out and risk losing a chance to host by endorsing an unpopular proposal.

In 1990, the IOC was meeting to determine who would host the 1996 Games, the centennial celebration of their revival. Athens made an official bid to be the host, and despite a lack of sufficient modern facilities and a significant air pollution problem, the sentimental appeal was obvious. Athens was the leader in the first three rounds of voting, as other finalists like Belgrade, Manchester, and Melbourne were eliminated.

But in the fourth round, the city of Atlanta, Georgia, suddenly leapt into the lead, and stayed in the lead for the decisive fifth round. While the city’s infrastructure and athletic facilities were rated highly, the IOC Members who advocated for it also argued that an Olympics in America, with events held in American primetime, would bring in more money from their television market. The Greek press, furious and insulted, made darker accusations that the Coca-Cola Corporation, a powerful Olympic sponsor whose global headquarters is located in Atlanta, had also influenced the process.

After the IOC was rocked by a wide-ranging bribery scandal, and a new group of organizers took over the Greek effort, there was a clear interest on all sides to try and restore some of the original luster of the Olympic spirit. Athens won the right to host the Games of 2004. And once again, it result was such a success, such a stirring reminder of the Olympic spirit, that Athens once again suggested that they could host the Games permanently.

As for the question of the status of the 1906 Games; decades passed without any consensus. The issue would occasionally arise at meetings, without any definitive action. Sometimes, they would be referred to as the Intermediate Games. Other times, it was falsely claimed that they were simply an athletic celebration honoring the 10th anniversary of the 1896 Games; even though there was no evidence that the Greeks who organized the event intended this.

It took until 1948 for the question to finally be resolved. Ferenc Mező was a historian and a poet from Hungary who belonged to the IOC. Like Baron de Coubertin, he was also an Olympic medalist, winning a gold medal for literature at the 1928 Amsterdam Games. His winning entry, in the category of “Epic Works”, was called “The History of the Olympic Games”. He cared passionately about the Olympic movement, and believed that the status of the 1906 Games needed to be settled once and for all. At an IOC session in 1948, he made an official motion.

Since the 1904 St. Louis Games had been the Games of the Third Olympiad, a proposal suggested that the 1906 Games be given the designation 3B, the second games of the Third Olympiad.

A special committee was convened, named the Brundage Commission after the man selected to chair it. If the Brundage Commission gave the matter serious study and reflection, we don’t have any evidence of it. They rejected the proposal in January of 1949 with a mercilessly short statement. Quote:

“It is not considered that any special recognition that the IOC might give to participants in these Games at this late date would add any prestige, and the danger of establishing an embarrassing precedent would more than offset any advantage.”

If the IOC considered it a dangerous precedent to give their approval to an Olympic Games held outside the four-year cycle, you have to appreciate the irony that we’re telling you this story now, as the world watches the 2020 Tokyo Olympics being contested in the year 2021.

PART FOUR

Did it have to turn out this way? Looking back down this dark path, I see so many moments where the 1906 Olympics could have received the official status they worked so hard to earn. If only they’d successfully held a second event. If only a few members of the IOC held different opinions at key moments, if more of Greece’s allies had made it to IOC meetings after Baron de Coubertin changed their locations, if just a few of the catastrophic military conflicts that continually rocked Greece had not left it so broken and bereft.

The movement to have an alternate Athens Games arrived at a delicate moment when there was just enough power left in the hands of Pierre de Coubertin that his strident and very personal opinions could hold sway. It all reminds me of what any high-level athlete will tell you about competition – no matter how hard you prepare, on any given day, the winds might turn against you. The ball might not bounce your way.

In Ancient Greece, one reason that the Olympiad was a four-year period was that it might take months for an athlete to travel to the city-state to compete; and that with that city-state’s fittest and best-trained citizens away, their army would be depleted and vulnerable. Amateur competitors couldn’t completely abandon their lives if the Olympics were happening too often.

But with modern technology and transportation, this is meaningless. And given the number of years most athletes can perform at their peak, a four-year gap means that they might get two or three shots at most in their lifetime to achieve their Olympic dreams. While it take far more than four years to prepare a city to host the Games, it’s still the responsibility of the host country and their NOC; so there wouldn’t be anything to stop overlapping preparations in multiple countries.

Maybe that four-year gap is just a tradition that feels right. Maybe it builds drama and anticipation for those all-important television ratings. And if you really have an appetite to see great exhibitions of sport, most of the events of the Olympics are being contested somewhere on a regular basis – the World Athletic Championships, for example, award medals in dozens of track-and-field events every two years.

For all the criticism we’ve levied at the International Olympic Committee, there’s no denying that the prestige and grandeur of the Olympic Games exist on a singular level. For just over two weeks we watch sports we would never otherwise care about, become deeply invested in the journeys and dreams of athletes we had never heard of before. Just attaching the word “Olympic” to an event gives it a status nothing else in the world can match.

And perhaps that’s why it’s so painful to see the 1906 Games downgraded in this way. These days they’re known as the Intercalated Games, an unusual word for an unusual asterisk in the history of the modern Olympics. The Brundage Commission claimed that giving those Games Olympic status over 40 years after the fact wouldn’t give the athletes any additional prestige; this is false on its face since it’s clearly the prestige of the Olympic brand they’re trying to protect. Certainly it would mean something to Finland to say that Venne Järvinen won Olympic gold for them even while they were under Russian control; it would mean something to the people who visit Billy Sherring Park in Hamilton, Ontario, the runners who compete in the annual Billy Sherring Memorial Road Race.

Or, you could make the argument that, as powerful as they are, the IOC can’t do anything to diminish the triumph of the athletes who made their way to Athens to test their limits. Maybe the question of whether their medals count as Olympic medals would only matter at an auction. Try as they might to deny the legacy of what Greece did in 1906, the Olympic Games honor that legacy every time the athletes parade into the stadium for the Opening Ceremonies.

Baron de Coubertin himself once said, quote:

“The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.”

He might not want us appropriating his words for this particular cause; but even though in the official history books of the IOC, Athens lost this struggle, we will always remember that they fought well.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Emily Wolfe and Evadne Hendrix; and our audio engineer is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by our senior story editor, Nicholas Thurkettle. Our lead researcher is Alex Bagosy; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.