Stealing Trust & Cryptocurrency

Episode 41

Delve into the mysterious life and sudden death of Gerald Cotten, the founder of QuadrigaCX, once Canada's largest cryptocurrency exchange. It starts by tracing Cotten’s early interest in digital currencies and his founding of QuadrigaCX, which quickly became a key player in the cryptocurrency market. In December 2018, Cotten reportedly died from complications due to Crohn's disease while volunteering at an orphanage in India. His death plunged QuadrigaCX into chaos as he was the sole person responsible for the exchange's funds and passwords, losing access $190 million worth of cryptocurrency held in cold storage.

Script

This is the My Dark Path Podcast

When cryptocurrency first emerged as a concept—and then as something that the mainstream investor could buy and sell —people the world-over became instantly attracted to it. The definition of crypto is simply this – a digital or virtual currency that is secured by cryptography which makes it nearly impossible to counterfeit. While other currencies are issued by a government, crypto is theoretically are independent of government and immune to government intervention or manipulation.

So this idea of a currency that does not go through a bank, is accessible to everyone, and has a fully public record is enticing. It is especially enticing to those who had trouble trusting others with their money and don’t want to put their savings into the hands of a stranger at the bank or have their transactions monitored by a government. With Bitcoin, perhaps the most well known of any crypto currencies, you can do it all yourself.

Still, while cryptocurrency is technically accessible to anyone, it’s actually really complicated to understand if you’re not an expert. The average person needs a way to enter this game and come out a winner, even if they don’t fully understand what they’re doing. That means that average players need to rely on a third party to handle the high-tech stuff for them. But as long as it’s a company that’s transparent, that exists solely for the benefit of the consumer, then maybe, just maybe, it can be trusted too. Or can it?

In full disclosure, I invest in crypto, although “invest” might be too sophisticated a word for how I approach it. Investing in stocks requires trying to predict future company cash flows company and then estimating their value reflected in the price of a stock. More specifically, a company takes inputs and sells the output of that for more than it costs to make it—at least if you’re doing it right. And in that case, the company’s assets are visible and measurable. Even in companies that just create software or algorithms, the value is observable in the skills of the team that creates them. But crypto? There are no observable assets. Like gold and other precious metals, the price is completely tied to the value that others place in the scarce asset. The price of crypto rises and falls accordingly. But unlike, say, American gold eagle coins, which I can hold in my hand, crypto is just numbers on a screen; the asset’s existence is based exclusively on your trust that the company holding the bitcoins is trustworthy. Investing in crypto involves guessing the supply and demand for any particular cryptocurrency. So my investment strategy dollar cost averaging into a single cryptocurrency as a hedge against other investments.

At the end of the day, is cryptocurrency really that safe and secure? Are the people who own the money really the ones in charge of it? Is there more happening behind the scenes than the average person is aware of? It’s safe to say that wherever the opportunity to make money exists, so do big scams. And because of the nature of crypto, perhaps the risk is even higher in this brave new world of currency.

If someone asked you to picture a scam artist—someone who robbed innocent people of millions, who engaged in money laundering, who could potentially fake his own death—you would probably not picture Gerald Cotten. Thirty-year-old Gerry was a perpetual optimist with a sweet crooked smile who dressed in sweater vests and still played with Pokémon cards. He had a mop of shaggy blonde hair and soft blue eyes, a boyish face, and square-framed glasses. If you spoke with him, you might be struck by his confident and charismatic demeanor. You would certainly not feel intimidated. He came off as the friendly nerd next door. Sure, he also happened to be the founder of Canada’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, QuadrigaCX. But that wasn’t so surprising. This guy had a similar vibe to Mark Zuckerberg or even a young Bill Gates—a geeky boy genius completely capable of making it big in the tech world. He wasn’t anyone to be afraid of. Instead, perhaps, he was someone to look up to, to be inspired by.

Until he died. Or, uh, supposedly died? And the truth came out, one dark secret at a time.

In today’s episode of My Dark Path, we tell the story of Gerald Cotten: internet geek, YouTuber, and perhaps criminal mastermind. Serious cryptocurrency professionals have a mantra: trust no one. So why did they trust him?

Hi, I’m MF Thomas, and this is the My Dark Path podcast.

In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science, and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Find us on Instagram, visit mydarkpath.com, and see our videos on YouTube. But no matter how you choose to connect with us, I’m so grateful for your support.

Also, if you want more of My Dark Path, subscribe on Patreon! I’m releasing a new, subscriber-only episode every month. Our first 6 Plus episodes are covering the Secrets of the Soviets based on research I’ve done in Moscow. Plus, subscribers get free My Dark Path swag, such as T-shirts, books, and more. To celebrate the release of my latest novel, Like Clockwork, every Patreon subscriber, at the end of September, will receive a free autographed copy. I appreciate our subscribers so much as they help the show grow!

If you stay until the end of the episode, you’ll hear a special promotion for the Ghostly podcast. It’s one of our favorites here at My Dark Path.

Let’s begin with Episode 41, “Stealing Trust.”

PART ONE:

In January 2019, hundreds of people were facing a financial crisis. They had placed their bitcoin—hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth—into Cotten’s booming cryptocurrency exchange, QuadrigaCX. Quadriga had run into delays in transfers and withdrawals before, usually because of bank freezes and other logistical issues out of the company’s control. Sometimes, cash withdrawals were delivered to users in shoeboxes or giant envelopes because many Canadian banks refused to dabble in crypto. Its users were usually understanding. They liked Gerry. They trusted him. They appreciated that he went out of his way for them. And, of course, people are always more trusting when they are being told they’re making money . . . and lots of it.

That January, though, users started to get nervous—suspicious, even. They could place their bitcoin into the exchange without a cinch, but no one could get their money out of it. Millions of dollars in cryptocurrency were locked away, and unlike in the past, no explanation was offered. No shoe boxes delivered to the door. On the other end of angry voicemails, frustrated emails, and even inquiries from reporters was radio silence. Where was Gerry with his usual explanations? Where was Gerry with his promises to get things under control? Where was Gerry?

Then, on January 14, 2019, QuadrigaCX posted an update on its Facebook page: the founder and CEO, thirty-year-old Gerald Cotten, had unexpectedly passed away a month earlier on his honeymoon in India. He was the only person with the passwords to access the funds owed to QuadrigaCX’s users, totaling about a quarter billion US dollars. The money was inaccessible. Users, understandably, had questions. The first of these was, “When will I get my money?” and the second, “Why did it take a month to announce Gerry’s death?”

According to hospital records obtained by the Globe and Mail, just before Christmas in 2018, Gerry checked into a hospital during his honeymoon in Jaipur, India. The normally energized and jubilant thirty-year-old was lethargic and disoriented. He had vomited over a dozen times, had diarrhea, and they quickly diagnosed him with acute gastroenteritis. Not surprising, as my trips to that beautiful country have resulted in similar intestinal difficulties. But Gerry had it worse than most of us. He had Crohn’s disease, so stomach issues weren’t exactly a rarity. That he was young and otherwise healthy implied he should be out of the hospital in no time. But the vomit kept coming—so did the diarrhea. Soon, Gerry was dehydrated and in septic shock. He suffered three heart attacks. After the third, Gerry Cotten was pronounced dead. The official cause was complications with Crohn’s disease, although his doctor told a Globe and Mail reporter that he was “not sure” that was the correct diagnosis. No autopsy was requested.

To QuadrigaCX customers, the whole event felt sketchy. How could a healthy thirty-year-old drop dead in twenty-four hours from Crohn’s Disease? And how on earth did the head of a major cryptocurrency exchange not have a backup plan for his passwords in case of kidnapping, disappearance, or death? As worried investors—many of whom had put their life savings into Quadriga—began to ask questions, so did the government.

The Ontario Securities Commission, the FBI, journalists, and the embittered (and, frankly, screwed) users of QuadrigaCX conducted investigations. It was only a matter of months before the dark truth about the supposedly trustworthy founder was uncovered. As it turned out, the boyish and geeky thirty-year-old was an expert scam artist. And some believed he may have just pulled off the greatest exit scam in crypto history: faking his own death and running off with millions.

Initially, some found this theory hard to believe. Gerry was like a puppy dog. He posted videos on YouTube of getting lost in mazes at amusement parks and teaching toddlers how to use a Bitcoin ATM. He spent his honeymoon in India so he could open an orphanage there. He was a harmless, bighearted geek who had been endlessly loyal and committed to his customers. On the day of his death announcement, one QuadrigaCX user posted on Reddit that Gerry was “the rare honest type,” an essential leader in cryptocurrency who would be dearly missed.

No one—especially those who had trusted Cotten with their life savings—wanted to believe the harrowing truth.

Back in 2012, the terms “bitcoin” and “cryptocurrency” were mostly unheard of—only spoken about by a select few economy and tech whizzes. One such whiz was Gerald Cotten, a recent graduate of York University’s business program. Cotten was part of a club of about ten Bitcoin enthusiasts in Vancouver, who called themselves the Vancouver Bitcoin Co-Op. The club would meet regularly in cafés and college dorms to research and trade in Bitcoin, which cost only $100 at the time. According to an article in Vanity Fair, “most of these early acolytes were drawn to the digital currency’s libertarian ethos—its promises of decentralization, transparency, speed, and independence from governments and financial institutions.”

The early followers of Bitcoin truly believed it could save the world and thought of investing in it as a mission for the common good. At the time, they could never have imagined just how much it would blow up, or how rich they might become because of it. Or how they could lose everything.

Cotten believed in Bitcoin from the get-go and dreamed of introducing it to the rest of the world. There was just one problem—it was nearly impossible to understand for the average person. The world of cryptocurrency was complex, highly technological, a logistical nightmare. Cotten decided to make it user-friendly.

In 2013, with that goal in mind, Cotten and his good friend Michael Patryn founded QuadrigaCX. They jumped through hoops to get their company a business license from FINTRAC, the Canadian anti-money-laundering service. QuadrigaCX was the only Canadian cryptocurrency exchange with this distinction—making it the only officially trustworthy exchange for those who wished to dabble in Bitcoin. This is a big deal. Remember, trust is everything to Bitcoin traders. That official seal of trust was exactly the bait many needed to get hooked.

Quadriga was also easy to use. Anyone could figure out the website, even without the most basic knowledge of cryptocurrency, and it allowed small investors to participate. Additionally, there were few limitations on whata person could trade: QuadrigaCX allowed users to buy Bitcoin with gold that they could hand deliver to the company’s headquarters. That meant that the average person with no money in their pocket could trade in late Grandma Helen’s necklace for a crypto portfolio.

Unsurprisingly, QuadrigaCX quickly grew in popularity. There were some bumps in the road—Cotten’s cofounder left the company after an alleged disagreement about whether to take it public—but nevertheless, by 2014, Quadriga was the top cryptocurrency exchange in Canada.

Still, nobody—not even Gerry Cotten—could have anticipated what would happen next. In 2017, the price of Bitcoin skyrocketed to almost $20,000 a Bitcoin. Everyone wanted a piece of that pie, and most Canadians went through Quadriga to get it. People were trading in their life savings, their college funds, their retirement funds. In all, Quadriga processed almost $2 billion in trades from over 300,000 users that year. Cotten received a commission from every transaction—perfectly legal and normal—and he giddily engaged in a lavish lifestyle worthy of a king. Of course, looking back on this time, where people put every dollar they had into an investment, it’s easy to see the dangers. Whether it was the Teapot Dome scandal in 1922, Enron, or Bernie Madoff . . . con artists rely on irrational exuberance to reel in more investors.

So, that year, Cotten purchased a $600,000 yacht, a private jet, four mansions, fourteen rental properties, and a brand-new Lexus. He and his girlfriend, Jennifer Robertson, traveled the world together, with Jenn’s two chihuahuas in tow. Cotten did all his work on his laptop so he could work from anywhere, which is exactly what he did. In the documentary Trust No One: The Hunt for the Crypto King, a friend of Gerry’s explains that nearly every time he spoke with him, Gerry was in a different country. One day he was in Iceland; the next day, he was in Hong Kong.

While Cotten was living large, his company was suffering. After the surge in 2017, Bitcoin’s price dropped. By fall 2018, the price had dipped from $20,000 to just over $3,000. As I finish editing this episode, my tracker shows it at about $2,100. Traders were losing money fast. They wanted to withdraw, to get out before they lost everything. Quadriga users, however, couldn’t. And so, the excuses started. Computer mishaps and banking issues froze withdrawals. Millions of withdrawals were stuck in limbo. Traders watched in dismay as their life savings diminished before their eyes. Cotten offered brief apologies and promised that the issue would soon be resolved. There had been bank freezes in the past, and Cotten had got people their money, but this time felt different. The rate that Bitcoin was dropping was staggering, and the freeze didn’t seem like it would end anytime soon.

Around this time, Cotten married Robertson, and the two jetted off to India on honeymoon. No one heard from Cotten—who was now the sole person operating Quadriga—for a month. Then came the Facebook announcement. Cotten was dead. The money—$250 million—was inaccessible. This was more than the money frozen by the banks. It was every single dime deposited into Quadriga at the time, and the only person with the key—or password—to access it was dead.

At first, crypto enthusiasts mourned Cotten’s death. Still hopeful that they would receive their money, they offered sincere condolences on the internet, expressed gratitude to the genius who had helped them make a profit from Bitcoin, and lamented the tragedy of losing someone so intelligent so young. “We lost a real Bitcoin hero today,” one Redditer posted that January.

It was only a matter of days, though, before the alarm bells started ringing—signs that the money wasn’t coming back, that Gerry Cotten may not have actually died at all. At first, it was the small things: his name was misspelled by one letter on his death certificate. The casket was closed at the funeral, so no one actually saw his body. He made a will just twelve days before his sudden death. Not to mention the timing: what a coincidence that Gerry Cotten would die right as Bitcoin started dropping in price.

There were other inconsistencies too. The passwords to access the money supposedly died with Gerry, but Gerry had spoken in a 2015 interview about the importance of saving passwords somewhere secure in case of emergency. In another interview, he claimed to have installed a safe in his attic, where he kept his passwords. The safe—which had been bolted into the rafters—was gone.

Additionally, Gerry had told friends the same year he died that there was a “dead man’s switch” that would give them access to Quadriga’s accounts if he ever died or disappeared, but that was not the case.

Perhaps most alarming of all was the “cold wallets.” In crypto-lingo, cold wallets refer to the external hard drives used to store large sums of money. Cold wallets are not unlike a vault—they are rarely interacted with and hold most of the savings. When investigators searched for the cold wallets belonging to QuadrigaCX, they found no indication that the company ever had one. Without these hard drives, no one had a clue where the money was stored—or if it existed at all.

Michael Perklin, a friend of Cotten, who founded the world’s first blockchain security consultancy, told Vanity Fair that “Gerry was a very careful person who well understood the need to back up one’s private keys. There’s no way that a man like Gerry—with all his knowledge and his mindset—would leave it to chance.” That’s exactly what Gerry did, though, intentionally or unintentionally. He was the only person with access to the funds, and he established no backup plan whatsoever. So the negligence was unthinkable and, frankly, unbelievable.

While investigators pieced these bits of information together, users of Quadriga tried to solve the mystery themselves. They met on pages such as Reddit and Telegram, where they uncovered clues, scoured the internet for information, and tossed around conspiracy theories. Today, these chats have hundreds of users between them, including reporters, FBI agents, and creditors. But these first determined internet detectives discovered something altogether shocking about the case: Gerry Cotten was never the man he said he was. He was not just a crypto geek who happened to found his company at the perfect time. He was a scam artist—and possibly an evil mastermind. QuadrigaCX all too likely had been a scam from its very first day. And Gerry’s so-called “death” may just be its grand finale.

PART TWO: The Cofounder

Gerald Cotten may have been the sole owner of Quadriga at the time of his death, but back in 2013, when the company was born, he worked with a partner, Michael Patryn. As far as anyone knew at the time, Cotten and Patryn first met at a Vancouver Bitcoin Co-Op meeting. Patryn had reached out to the club one day, expressing an interest in joining. The group was so small —and Bitcoin so unheard of—at the time that members remember being surprised (even suspicious) to receive that message.

One club member, Joseph Weinberg, who was in college at the time, told Vanity Fair that Patryn’s sudden appearance was “weird.” Not only was it unclear how he even found out about the club, but he also seemed to be lying about his identity. Weinberg said that Patryn was unclear about where he came from. Some days he said he was from India, other times Pakistan, other times Italy.

Not only that, but Patryn had an imposing presence. He was demanding, severe, and power-hungry. Cotten seemed to shrink when he was with him, his bubbly and bright persona transforming into something more desperate and overeager. He laughed when Patryn wasn’t being funny. He followed Patryn around. He submitted to Patryn. Their power dynamic in their relationship made the others uncomfortable.

Patryn remained a mystery in many ways to his fellow club members, but one thing was for certain: Patryn had money. He drove around Vancouver in luxury sports cars. His social media showed photos of him riding an ATV in the desert and chilling with an actual tiger. No one knew exactly how he earned this money, but he sometimes made remarks about seedy connections and a dark past.

As internet detectives dug into Cotten’s—and by proxy, Patryn’s—past, they discovered that Michael Patryn was actually Omar Dhanani, who had been convicted of credit and bank card fraud in a major sting operation by the US Secret Service in 2005. After his release from prison, he was deported to Canada, where he changed his name twice: first to Omar Patryn and then to Michael Patryn. In addition to this alarming discovery, something even more haunting was uncovered: Cotten had not, in fact, met Patryn for the first time at the Co-Op meeting. They had met much, much earlier.

The Quadriga creditor who made this discovery goes by QCXINT on Telegram. QCXINT told Netflix that he “had probably more funds in [Quadriga] than I was strictly comfortable with . . . so I guess being personally involved with this story, I was highly incentivized to find out what had happened.” In the months following Cotten’s death, QCXINT threw himself into investigation mode, digging into archived web pages and decoding encrypted message boards.

One website he found on his search was TalkGold.com, a board dedicated to Ponzi schemes. Scam artists and people looking to make a quick return on an investment frequented the site. As Vanity Fair put it, “TalkGold was a Ponzi clearinghouse, where blind faith and curdled cynicism engaged in a demonic rumba.” The site boasted forums where scam artists would offer each other advice on how to create the perfect exit, how to make the most profit, what type of people to target, and how to reel them in.

So why is TalkGold relevant? Well, once QCXINT found his way to the since-deleted and archived website and wiped the dust off, he and a few fellow investigators discovered that both Patryn and Cotten had profiles on TalkGold. Not only that, but the two had used the website almost obsessively (Cotten posted around four times a day) and had a history of chatting with each other and promoting each other’s posts on the site. Their activity on the website—and communication with each other—dates back to 2003, when Cotten was just fifteen years old.

At the beginning of their relationship, Cotten had tried to scam Patryn, and Patryn had tried to scam Cotten right back. They impressed each other. Soon, they were friends.

In January of Cotten’s freshman year of high school, he began his first pyramid scheme called S&S Investments. The site promised a return of “103% to 150%, possibly more” within forty-eight hours. The “about” page even had a disclaimer: “We are not what is called a Ponzi or pyramid scheme.” Cotten took down the site after just a few months, pocketing any money users put into it. Patryn, twenty-one at the time, was impressed.

Around this time, the Secret Service arrested Patryn and put him behind bars. Still, being in prison did not end his friendship with Cotten. By 2007, he was free and back on the forums. He and Cotten developed a shared interest in digital currencies and decided to go in on an operation together. They started Midas Gold—an independent payment processor for Liberty Reserve, a digital currency that, according to Vanity Fair, “was operated by an American in Costa Rica and used by drug cartels, human traffickers, child pornographers, and Ponzis to launder money.” Through Midas Gold, anyone who dealt in Liberty Reserve could transfer and withdraw their money anonymously. Midas Gold kept no record of its users or their history.

Then, in May 2013, law enforcement across seventeen countries shut down Liberty Reserve altogether, arresting its administrators and freezing its finances. Midas Gold was seized in the sting.

This mattered little to Cotten and Patryn. They had already moved on to bigger and better things, having started on the Quadriga Fund that same year. Quadriga would be their biggest venture yet; everything that came before, all the scams and fraud and lies, had just been practice. Cotten and Patryn were experts by this point—not just in running schemes but in baiting the hook that would gain consumers’ interests in the first place. “When you invest in Quadriga,” the company’s shiny new website read, “you remain in control.”

They knew the exact language to use to gain the trust of those who were notoriously committed to not trusting anyone. “Wealth is freedom,” the site said. “Your money is safe here—it’s yours.”

Still, the company seemed to be missing something. According to QCXINT’s findings, in October 2013, Cotten made one final post on BlackHatGoods—a forum dedicated to fraud and stolen goods. It was a job post searching for someone “familiar with Bitcoin” to help develop a website for a new company where people could buy and sell the cryptocurrency.

Within three weeks of making this post, Cotten changed the name Quadriga Fund to QuadrigaCX and opened for business.

At the time, he and Patryn may have thought they’d be operating just another quick scheme—bigger than the last ones, yes, but not that many people knew about Bitcoin yet, so it would likely remain small and manageable. They had no idea what they were really in for.

PART THREE: The Ultimate Scam

So what exactly was QuadrigaCX? As far as consumers knew, it was an easy and safe way to buy and sell bitcoin, to make deposits and withdrawals of the electronic currency without the headache of dealing with a bank—most of which didn’t accept crypto, anyway.

In many ways, it was also the perfect front for a scam. QuadrigaCX was made for the average person—consumers who wanted an “in” with cryptocurrency but weren’t expert enough to completely understand what they were doing. People also expected things to go wrong. Because banks didn’t deal in crypto, it was reasonable to think that there might be money freezes from time to time. When a trader couldn’t get their funds, they blamed it on the government before they blamed it on Gerry.

Gerry was the good guy—the friendly neighborhood CEO who appeared on his customer’s doorsteps with a shoebox filled with the cash he owed them.

But how exactly was he getting this cash in the first place? Sometimes, customers’ money would be delivered to them while other customers were still waiting for their payday—still being told the funds were frozen. How could the funds be frozen for one trader but not the other? It seemed that whoever complained the most publicly got their money fastest. And of course, this is the essence of a Ponzi scheme, using new investors’ money to pay off the requests of old investors. And it always works . . . until the withdrawals exceed the new investments.

Gerry Cotten, of course, was no amateur when it came to scams. He had been developing successful exit scams and Ponzi schemes since he was a freshman in high school. At its roots, QuadrigaCX was no different from the small-time exit scams he used to perform. It was just bigger—a lot bigger. The truth was, back in 2013, when Bitcoin was not yet a household term, Cotten could never have predicted just how popular it would become. It would almost be understandable if, by 2017, Gerry was forced to make some rash decisions to keep up with his influx of customers.

That’s not quite what happened, though. Investigators discovered that as early as 2015, Gerry was stealing from QuadrigaCX users, either for his own greed or to keep up with demand (or both). Not only that, but he used falsified Quadriga accounts to trade for real bitcoin, US dollars, and Canadian dollars, acquiring real assets of his customers for nothing. In all, these fake accounts were used for over 300,000 trades on the website.

The biggest red flag may have been QuadrigaCX’s headquarters and record keeping. Traders described the office as a single, tiny room with a couple of desks in it. Not exactly what one might expect from a billion-dollar company. The company kept no records and did not pay taxes. Again, this is almost inconceivable for the type of business Gerry was running.

Then there was the matter of the cold wallets—remember, the external hard drives that function as a vault for crypto—not existing. The cold wallets should have had around $200 million in them at the time of Gerry’s death. Eventually, they discovered this money divided messily throughout Gerry’s personal accounts in other cryptocurrency trading companies! As Vanity Fair put it, “It was the behavior of a doomed gambler” frantically throwing money anywhere he could, making things worse in a pathetic effort to make them better.

By the time of Gerry’s honeymoon in India, he was rapidly running out of options. With so many ripped-off customers and no solution in sight, he would need to come clean soon. Or he could fake his own death, not deal with the problem at all, and take the missing money with him: the ultimate exit scam. The Globe and Mail put this theory to rest when journalist Nathan VanderKlippe traveled to India, spoke to the doctor who worked on Gerry’s case, and got a thorough timeline of his stay in the hospital. This is the story we told at the beginning of this episode: Gerry arrived with stomach pains, had three heart attacks, and died.

Still, some people have their doubts. After all, if Gerry randomly died, why was his safe missing from his attic, where it had been permanently bolted into the rafters? Why did he create a will just twelve days before the trip? Why had Gerry spent the last year of his life visiting dozens of countries around the world, where he easily could have been distributing funds into foreign bank accounts? Why was his name spelled wrong on the death certificate? Why did it take so long to announce his death? And finally, how could his death even be proven when nobody had actually seen his body?

Since Gerry’s supposed death, rumors have swirled around about his possible whereabouts. Some claim he is on a beach somewhere in the Caribbean, with a new face created by a well-paid plastic surgeon. With enough money, anything is possible. Even vanishing altogether. If this is what happened, we can only wonder if he did it because he found himself in a corner, unwilling to face the consequences of his failing company, or if this was an exit scam he had dreamed up since the beginning.

Gerry’s wife, Jennifer Robertson, forfeited the assets she inherited from her late husband to affected Quadriga users. She has been cooperating with the investigation and told reporters that she would simply like to “move on with her life.” She claims she had no idea of Gerry’s illegal activity, although her property management business had received transfers from Quadriga traders while the company was operating.

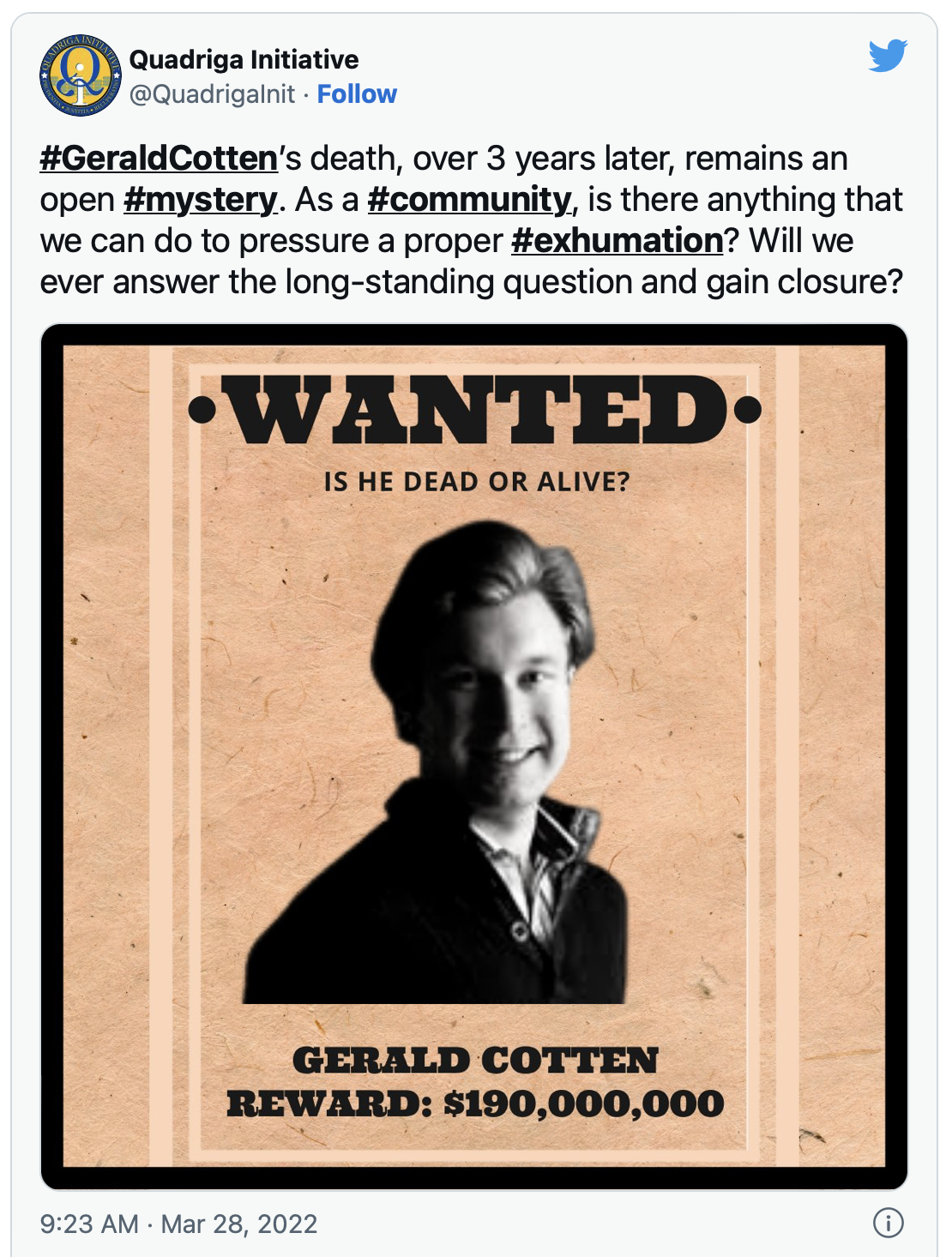

Even with Robertson’s contribution, it doesn’t look good for most of the people who lost money in Quadriga. In all likelihood, they will never get back everything they are owed. Many of them want Gerry’s body exhumed so they can find out once and for all if the scam artist really is dead. Until that happens, we may never know the truth about what happened to Gerry Cotten. He could be anywhere, and he could be nowhere at all. The nature of his life and the uncertainty of death are reminders that our investments in idolizing people and chasing any get-rich-quick scheme are worth caution.

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, the creator and host. I produce the show with our creative director, Dom Purdie. This story was developed by Laura Townsend. Big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team. Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a rating and review wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science, and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.

References & Music

A moment of silence for Gerald Cotten. We lost a true Bitcoin hero today

Did Gerald Cotten fake his own death?

Don’t Believe the Conspiracy Theories About “Crypto King” Gerald Cotten’s Death

How did Gerald Cotten die? A Quadriga mystery, from India to Canada and back

Ponzi Schemes, Private Yachts, and a Missing $250 Million in Crypto: The Strange Tale of Quadriga

Quadriga CEO's widow speaks out over his death and the missing crypto millions

Quadriga CEO's widow to return $12 million of estate assets in voluntary settlement

QuadrigcaCX CEO Gerald Cotten has died due to complications with Crohn's disease

Trust No One: The Hunt for the Crypto King

Trust No One: The Hunt for the Crypto King directed by Luke Sewell

Widow of Quadriga crypto founder Gerald Cotten says she had no idea about the $215-million scam

Industry, Falls

Brenner, Falls

Reign of Terror

Revival, Daniele Musto

Joy to the Synthwave World, Falls

Images