Episode 4: Elmer McCurdy’s Second Life

How does someone’s corpse get so exploited and degraded that, decades later, everyone mistakes him for a prop?

After Elmer McCurdy’s death, his embalmed body was exploited as a sideshow attraction, a movie prop, and ultimately a decoration in an amusement park’s haunted house.

Thomas Edison in 1911. His multiple patents on motion picture technology enabled him to monopolize the early film production industry, encouraging those determined to illegally use his technology to flee westward.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Screenshot from The Great Train Robbery. The end scene, right before the actor Justus D. Barnes points and repeatedly shoots at the camera.

Edwin Stanton Porter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The northwest corner of Gower St and Sunset Blvd, photo taken 1911 in the month that David Horsley arrived in Hollywood prior to setting up the first film studio there at this very location. Also the same month that Elmer McCurdy was shot and killed in Oklahoma during an attempted train robbery.

Unknown author, collection of Earl Theisen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nestor Studios. Same location two years after prior photo.

Witzel Studios, LA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gower Gulch as of 2006. Across the street from Nestor Studios, this is where people would gather in the hopes of being cast in the westerns that David Horsley’s team attempted to churn out on a weekly basis.

Gary Minnaert, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Elmer McCurdy within a few years after embalming by Joseph L. Johnson.

W. G. Boag, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The location in Pawhuska, Oklahoma where Joseph L. Johnson embalmed Elmer McCurdy and eventually made use of his corpse as a tourist trap.

Laura, Quirky Driven Life

Diagram of Elmer McCurdy from the autopsy performed my Dr. Joseph Choi on December 9, 1976 after his body was rediscovered to not be an artificial prop.

Oklahoma Territorial Museum

Burial of Elmer McCurdy at Boot Hill, Guthrie, Oklahoma.

Oklahoma Territorial Museum

Elmer’s (hopefully) final resting place at Boot Hill in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

Laura, Quirky Driven Life

View from the first Ferris wheel at the Midway Plaisance at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. This was considered the originator of modern traveling carnivals.

E. Benjamin Andrews, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Front marquee of the Hollywood Wax Museum. Sapuran “Spoony” Singh Sundher, bought the body of McCurdy one year after opening.

Momwriter, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

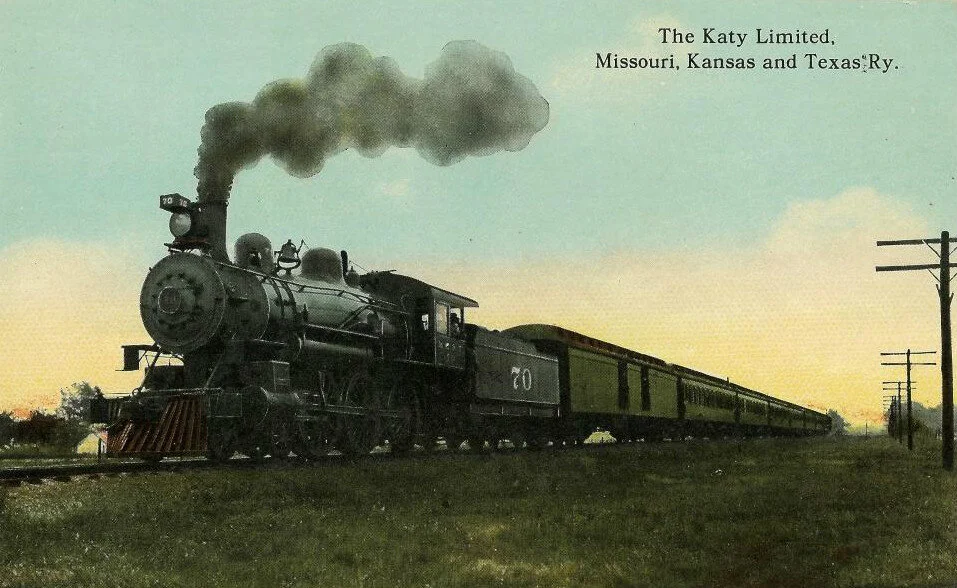

A postcard illustration of the Katy Limited, a KATY train such as those targeted by McCurdy on the premise of being high value, albeit not without high risk.

UNICO, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Another illustrated postcard of one such KATY passenger train as potentially robbed by McCurdy. Postmarked July 4, 1911—exactly 3 months prior to McCurdy’s final robbery.

UNICO, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Full Script

INTRODUCTION

To most people, Los Angeles is synonymous with Hollywood - the show business capital of the world. It’s the Dream Factory that brings us the movies and television shows that shape our lives. Famous landmarks, like the Hollywood Sign and Grauman's Chinese Theatre, are icons of this storied place. And every day more artists and dreamers arrive in town, hoping to be a part of it all. Like other magnets of innovation, there’s a unique creative energy in LA that elevates everyone – even low-skill, high-aspiration creatives like me.

Hollywood’s reputation almost guarantees (to use a Hollywood term) a “boffo” business in tourists seeking to experience the magic. When you walk along Hollywood Boulevard, you see star shapes embedded in the sidewalk, commemorating showbusiness legends. You can buy a miniature plastic Oscar statuette with your name on it. You can also, for a few bucks, pose for a picture with someone in a Spider-Man costume.

Yet for every example of Hollywood’s artistic triumph and glamour, there's also an underbelly, something more sensational or cheap, ready to exploit our baser appetites, to hustle a few bucks out of our pockets. It's the sideshow to the bright, friendly circus. Just across the intersection from the glamorous Hollywood & Highland shopping center are more some of the milder garish attractions - like the Ripley's Believe it Or Not Museum, or the Hollywood Wax Museum. There’s much more lurid entertainment but it doesn’t advertise itself quite so aggressively.

Filmmaking in Los Angeles didn't start here on Hollywood Boulevard; to find the spot where it all began, you have to go about a mile east, to the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street. It was at this exact intersection, in October of 1911, that Nestor Studios opened its doors. The previous year, D.W. Griffith had shot a few films in and around Los Angeles, but he'd returned to the East Coast, which was the center of the movie business back then. Nestor Studios was the first permanent movie studio in Los Angeles. It shot its first movie six days after opening for business. Other studios soon followed, and Hollywood started growing into the entertainment juggernaut it is today.

Meanwhile, that very same month, October of 1911, 1,500 miles away in the Osage Hills of Oklahoma, an outlaw named Elmer McCurdy died in a shootout. His story, in the strangest of ways, gives us a glimpse at that other side of Hollywood, the wilder and weirder version of showbusiness that lures us off the boulevard of stars. The side that takes you down a dark path.

Because you see, when Elmer McCurdy got hit by a deputy's bullet, it was the end of his life. But it was the start of his very long career in showbusiness.

***

Hi, my name’s MF Thomas; I’m an author and a lifelong fan of strange stories from the dark corners of the world.

This is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these topics….you’re among friends here at My Dark Path.

As we grow the podcast, we’re expanding the collection of photos we post to help illuminate every episode. To see them, visit MyDarkpath.com When you’re there, register for the My Dark Path newsletter and you’ll be entered for frequent drawing for a unique book or other oddities from my personal cabinet of curiosities. At the time of this episode’s release, we just drew the name of the first winner. Checkout the newsletter to see what oddity this winner selected.

With all that business wrapped up, let’s get started with Episode 4, Elmer McCurdy’s Second Life.

***

PART ONE

A daring gang of outlaws slips aboard a train in broad daylight. A quick-thinking security man throws the key to a strong box off the train, before dying in a shootout with the gang of criminals. Without a key, they blast the strong box open with gunpowder. The gang's leader viciously bludgeons the head of the train engineer, before hurling his body from the train. Passengers are lined up to have their valuables taken. One tries to run away and is shot in the back. The gang of thieves find their waiting horses and escape into the woods. But as they're focused on the loot they've stolen, a posse catches up to them, and guns them all down. Justice prevails.

Sounds as exciting as a movie, doesn't it? Well, it is one of the most influential American films of all time. It's called The Great Train Robbery, made by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company in 1903. It runs about 12 minutes long, an epic when most films ran a minute or less. It's got action, stunts, comedy, gunfire, an explosion, and an infamous closeup, where the leader of the robbers aims his gun directly at the camera, and fires. This movie was made only 8 years after the very first public exhibition of moving pictures by the Lumière Brothers in France. Some of their audiences were sent into a panic just by moving images of a train pulling into a station. It looked like the train was coming right for them. Now, just eight years later, the movie screen was holding them at gunpoint.

To make a Western in the early 1900's, you weren't making a period piece. The Wild West was still a real place, and stories of shootouts, robberies, and chases on horseback were contemporary crime thrillers just like any current true crime or police procedural TV show that you would watch today. And audiences loved it. Once the movies started telling stories, Westerns immediately became one of the leading genres.

The Western expansion, which is such an inseparable part of the story of America, happened at the same time that our culture embraced several important technologies and popular trends. This all cemented the frontier as the home for American mythmaking. The year 1860 saw the publication of the first American dime novels - cheaply-produced, melodramatic tales that were made for the common citizen - someone who didn't have the luxury to burrow deeply into a dense volume of great literature - but wanted something fast and entertaining. They were the American version of England's penny dreadfuls. The very first dime novel was a Western, and the flood of Western books that followed ignited the public's imaginations with stories of gunfighters and gamblers, of saloon brawls and bare-fisted lawmen.

In addition, by the end of the Civil War, the Union Army had laid over 15,000 miles worth of telegraph wire around the country, giving them a communication advantage that the Confederacy couldn't match. And after the war, it brought on a communication revolution - for the first time, a story happening out West could make its way back east faster than horseback. Now the news and the legends about what was happening on our frontier, served as an unending source of fascination and drama that people in the east could enjoy vicariously.

And then, the movies arrived, and took all this mythmaking, all this feverish interest in the West, and made it larger-than-life on-screen. It's funny to think that "The Great Train Robbery", that 12-minute thriller that audiences loved so much, wasn't actually made out West. It was mostly filmed in New Jersey.

Filmmaking in America lived on the East Coast back then, largely because of Thomas Edison. He held several crucial patents on motion picture technology and exercised that power ferociously to squeeze competitors out of the marketplace. A filmmaker trying to work anywhere in the Northeast without his permission could find themselves visited with legal threats, or even a bully mob breaking up the production and seizing their equipment. Plus there was the other problem - the weather. Making a movie back then, you couldn't even get started without adequate sunlight; and the winters in New York didn't provide much of that.

It was a producer named David Horsely, who had established a small studio making short comedy films based on the beloved newspaper comic strip Mutt & Jeff, who heard about D.W. Griffith visiting Los Angeles to shoot a few films. Horsley wasn't any kind of artist, he was an entrepreneur who had sold bicycles and run a pool hall; but he sensed an opportunity in this rapidly-growing business. He decided to take a great gamble - he would open a full-time, professional studio, in a place no one had heard of - Hollywood.

In 1911 Hollywood was, in a sense, the wild west of Los Angeles. It was ten miles west of the city proper, separated by barley fields and citrus groves. Only one road connected them, and if you didn't have a horse, a trip by streetcar could take over two hours. It sounds absurd to say now, but back then, land was cheap and plentiful, which allowed studios to build massive lots with production stages. And outside the stages, there were spectacular mountains and forests and beaches nearby to capture on film, and the sun was shining all year round.

Hollywood had one additional advantage - a working telegraph wire. If Thomas Edison sent agents out to bust up a film shoot, an observer on the train platform in Los Angeles could spot them arriving, and wire ahead to his comrades at the studio, giving them a head start to wrap up and hide. Sometimes they would flee all the way across the Southern border into Mexico, where Edison's patents didn't apply, and their expensive equipment couldn't be seized.

Hollywood was, in a real sense, an outlaw operation, and David Horsley was the first outlaw in town. When he opened Nestor Studios, the number one job he gave his team was to shoot a Western picture every week. To this day, the land across the street at Sunset & Gower is known as Gower Gulch. Every day, real cowboys, or just people who owned cowboy clothes, would gather there, hoping to be grabbed as extras, stunt people, or maybe the next big Western star. Today, Gower Gulch has a drug store, a noodle shop, and a Starbucks, where maybe an aspiring screenwriter is writing his or her own Western saga.

Elmer McCurdy never made it to Hollywood when he was alive. See, at the same time that David Horsley was making a new movie every week, replete with gunfights and train robberies, Elmer McCurdy was robbing trains for real.

***

PART TWO

We're going to do things backwards with Elmer McCurdy. His fame came after his natural life ended, but we're going to talk about his fame first. You see, nobody came to claim McCurdy's body after he died in that shootout in Oklahoma. The local undertaker in Pawhuska, Oklahoma was a man named Joseph L. Johnson; and he refused to release the body until somebody paid him for his work. He embalmed the body of Elmer McCurdy with a cutting-edge formula, primarily using arsenic. He then decided to take this bad luck, of an unclaimed body, and turn it into an opportunity.

He propped up the body of McCurdy in his shop in order to show off the quality of his embalming technique. It wasn't often that you got a relatively young, fit corpse - there was nothing wrong with McCurdy's body but the bullet that killed it. It made him a good spokesmodel. Hordes of curious visitors began to fill the shop, and Johnson realized that not all of them were likely to need embalming services anytime soon. But they were drawn to the ghoulish spectacle of this dead crook. Johnson moved McCurdy's body to the back room; according to some accounts, the fee to see his body was a nickel, and you had to put the nickel in his mouth, if you dared.

Johnson had, quite by accident, created a tourist trap. It was around this time, it's believed, that McCurdy's body was given the nickname "The Bandit Who Wouldn't Give Up". The thing about a good name is this - people start to make up their own story of how it came to be. It provides an aura of mystery - you can picture it as the title of one of those Western dime novels - "The Bandit Who Wouldn't Give Up".

Johnson kept collecting nickels from passersby for five years. One story says that by this point, Elmer McCurdy's body was so stiff from the arsenic that he could be propped up on rollerskates. Johnson had been in a hurry to be rid of McCurdy five years ago, but he had certainly become a lucrative side business. Finally, though, he turned over possession of the body, believing that the chance had finally come to lay him to rest.

There are different versions of what happened, but McCurdy's body didn't get buried like Johnson believed he would. He wound up in the possession of James Patterson, the owner of a traveling carnival. In some versions of the story, old members of McCurdy's gang claimed the body and then resold it. In another version, Patterson himself came to the Johnson Funeral Home, claiming to be Elmer's long-lost brother.

Whatever swindle he worked out, James Patterson shipped Elmer McCurdy's body to Arkansas City, Kansas, to become an exhibit in the Great Patterson Carnival Show. They even gave McCurdy's nickname a little added flourish. He went from "The Bandit Who Wouldn't Give Up" to "The Outlaw Who Would Never Be Captured Alive".

Carnivals were a booming form of entertainment across America and had been ever since the Midway at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. There were dozens of major carnivals crisscrossing the country all year round, and every one of them was competing for sensational, strange, and macabre attractions. And as the Patterson's scheme proved, they were willing to play dirty.

The Pattersons featured "The Outlaw Who Would Never Be Captured Alive" for six years. Then, while we don't know the details; it seems they fell on hard times, because they used the body of Elmer McCurdy as collateral for a $500 loan. Which they never paid back. Now an ex-police officer named Louis Sonney had a dead body he needed to make some money off of.

This wasn't new territory for Sonney, though; he'd been charting his own path through the exploitation economy for years. After he had left the police force, he happened to stumble across a fugitive bank robber named Roy Gardner. He captured Gardner, collected a handsome reward; and then used that reward to produce a silent film about his own heroism. The movie was called, naturally, I Captured Roy Gardner. Maybe these days he would have produced a true crime podcast.

Sonney seems to have had a knack for self-promotion, and for leveraging his audience's hunger for lurid tales about outlaws. By the time he took possession of Elmer McCurdy's body, he had a whole traveling exhibit he called the Museum of Crime. It featured wax replicas of legendary outlaws like Jesse James and Billy the Kid. And now he had the real body of a not-so-legendary outlaw. But audiences didn't need to know that last part.

Traveling with Sonney, Elmer McCurdy went further than he ever had in life. The Museum of Crime became part of the official sideshow of the first-ever Trans-American footrace in 1928. Joggers started out in Los Angeles on March 4, 1928, and ran over 3,400 miles in 84 days, ending at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Out of 199 runners who started, only 55 finished. Newspapers called it the Bunion Derby. And every step of the way, they were accompanied by the Outlaw Who Would Never Be Captured Alive.

With audiences clamoring for him everywhere, it's no surprise that Hollywood would soon discover Elmer McCurdy.

In 1933, Louis Sonney loaned, or more likely rented, McCurdy's body to a fellow filmmaker named Dwain Esper. Dwain Esper was one of the earliest examples of the true exploitation filmmaker - making cheap, shoddy films with shocking titles and shameless displays of nudity and violence. He made a short film called How to Undress in Front of Your Husband, which starred Elaine Barrymore, the fourth wife of acting legend John Barrymore. John Barrymore sued to try and stop the release of the film, failed, and then divorced Elaine. Dwain Esper carried on undaunted - and a movie he made called Sex Maniac is described by many as the worst motion picture ever made.

Esper had a very specific idea in mind for the body of Elmer McCurdy. The corpse was nearly mummified by this point, shrunken and shriveled from the embalming chemicals and years on display in the open air. Dwain Esper's latest film was called Narcotic!, complete with exclamation point, and he pitched it to audiences as a shocking expose of the dangers of drug addiction; as the main character, a respectable doctor, gets addicted to opium, and spirals downward into a world of bordellos, cheap hustles, and carnival snake oil.

Elmer McCurdy's body, in a coffin, was propped up in the lobby of a Los Angeles movie theatre, where Dwain Esper would tell shocked moviegoers that this withered, horrifying cadaver with its paper-thin skin belonged to a drug addict who had been shot while robbing a pharmacy. People were appalled, people were horrified. People bought tickets.

McCurdy even appeared as a prop onscreen in one or more low-budget horror films, although the record-keeping in this world is shoddy to say the least so we only have one confirmed - a 1967 film called She Freak. Yes, I said 1967. Over fifty years after his death, Elmer McCurdy's body was still in circulation.

After the death of Louis Sonney, the corpse passed to his son, Dan Sonney. Dan Sonney stayed in the family business most of his life, making cheap, nudity-laden comedy films with titles like A Virgin in Hollywood and Knockers Up. McCurdy doesn't seem to have been of major interest to him - the body had suffered considerable damage over the years, and efforts to keep him presentable just made him look stranger and stranger. Once, while he was on display in a sideshow at Mt. Rushmore, a strong wind blew off his fingers.

In 1966, Dan Sonney finally sold the body, to one of Hollywood's most colorful characters of the 60's, an entrepreneur who called himself Spoony Singh. His full name was Sapuran Singh Sundher, and he came from a small farming village in India. But in Hollywood, where you can be anything you imagine, Spoony Singh saw how much tourists loved the star symbols embedded in Hollywood, and the handprints in the concrete outside the Chinese Theater, and he came up with an idea to let tourists get even closer to the stars they adored. He bought an empty brassiere factory on Hollywood Boulevard and turned it into the Hollywood Wax Museum; the same one I mentioned in the introduction that you can still visit today. It's just a few steps away from the theater where they hold the annual Academy Awards. Real stars may be in Hollywood just one night of the year, but their wax doppelgangers are always in-season.

Spoony Singh had the idea to show off McCurdy's body, either in the Wax Museum or in some future attraction; there's information to suggest that he did go on display in a coffin, briefly, but he eventually decided that the corpse just looked too strange now. Parts of his ears were gone, and his toes were lost now, too. He sold it to Ed Liersch, one of the owners of The Pike, an amusement park south of Hollywood in Long Beach.

And as far as we can tell, Ed Liersch genuinely did not know that he was purchasing an actual dead body. He put a fresh coat of paint on Elmer McCurdy's body, and put him on display on the Midway. Later, he draped a noose around McCurdy's neck, and hung it inside the park's haunted house attraction, which was called "Laff in the Dark". For years, tourists looking for a little scare were seeing an actual corpse, and never knew it.

Elmer McCurdy had one final brush with showbusiness. In 1976, a film crew from the TV series "The Six Million Dollar Man" was preparing to shoot an episode at the Pike. As the production design team was preparing the haunted house as a set, one of the crew tried to move the strange-looking mannequin dangling from a gallows. And when they grabbed it, its arm ripped off, revealing a human bone inside.

The forensic investigation into the origin of this mannequin was one of the strangest in the history of the Los Angeles County coroner's office. The jacket of the bullet that killed Elmer McCurdy was still embedded in his chest, which helped narrow down when he had died. They found vintage pennies stuffed down his throat, even ticket stubs from The Pike, as well as Louis Sonney's old Museum of Crime. Dan Sonney was located, and helped them confirm the identity of the bizarre, mutilated corpse. In 1977, a funeral procession was held in Guthrie, Oklahoma, and Elmer McCurdy's body was finally laid to rest, in the Boot Hill section of the cemetery, the area reserved for the most notorious gunfighters. While unknown in life, being the subject of decades' worth of yarn-spinning and hucksterism, with more than a little help from Hollywood, Elmer McCurdy had become a Western legend.

***

PART THREE

The interesting question is, should we consider McCurdy a legend? Should he be buried in Boot Hill, or is this just another perpetuation of the escalating myths told about him since his death? When you look up his name, you usually get some variation of the curious yet true tale I just told you. Meanwhile his actual life is summarized and dismissed quickly so that readers can get to the astonishing story about his remains. He's described as a hapless drunk, an inept bungler who committed the most unsuccessful train robbery in history before dying alone in a barn in a stupor of whiskey.

Does it matter if he was a true outlaw or bumbling amateur? Does it make it easier to justify our entertainment if he were the latter? Exploitation requires that we dehumanize someone, but the illicit thrill of exploitation wears off quickly once we start thinking about the person.

So, we decided to take a deep dive into the real life of Elmer McCurdy. Not the bullet point summary, not the source Hollywood entertainment, and not the legend of a pathetic failure, but a genuine study at what we could find about his actual years on this planet. It’s an opportunity to treat someone – now long dead – as we’d like to be treated a century from now.

Elmer was born in Washington, Maine, in 1880. His mother was Sadie McCurdy, just 17 and unmarried at the time of his birth. Sadie's brother, George, and his wife, Helen, adopted Elmer, to save Sadie the shame of having given birth to a bastard. We don't know the true identity of Elmer's father, but later in life he sometimes used the alias "Charles Smith"; which was the name of a cousin of Sadie's; and one of the people suspected of possibly bring the real father. Sadie lived with George and Helen, and little Elmer called her his aunt.

When George, the man he knew as a father, died of tuberculosis, Sadie finally told him the truth. After these two shocks, Elmer began to struggle with alcoholism, a sickness which he never completely shook.

He apprenticed as a plumber, and made a good living for a few years, though this was during one of the worst depressions in American history, following the Panic of 1893, and eventually he became dependent on his family again. In 1900, Sadie passed away, and Elmer McCurdy became an itinerant worker, taking plumbing work, working a lead mine, whatever he could find. He eventually reached Kansas, working as a plumber in Cherryvale. In 1901, he was arrested for public intoxication. His struggles with drinking made it hard to hold a permanent position anywhere, but he kept on finding a way to support himself.

In 1907, he enlisted in the Army at Fort Leavenworth. We don't know what prompted this decision, although he was having increasing brushes with the law, and even then it was often the case that a judge might suggest that serving the nation could help put someone back on the straight and narrow.

This is where I have a real problem with the depiction of Elmer McCurdy as a hopeless drunk - the U.S. Army in 1907 was deliberately kept very small, and they weren't desperate for recruits.

In addition, Elmer McCurdy was trained as a machine gun operator, and then trained further in the handling of nitroglycerin. These were highly technical and exceptionally dangerous jobs, and you wouldn't hand them out to someone who was at risk of blowing themselves up. All the available evidence suggests that McCurdy served capably and was able to keep his drinking under control while in the Army. After three years, he was honorably discharged; again not something that happens if you're a habitual troublemaker. There are even hints that he wanted to stay in the military, but longer enlistments were rare back then. Elmer McCurdy was a free civilian once again. This was November 7th 1910; 11 months before his death.

Just twelve days after his discharge, Elmer McCurdy and a friend from the Army were arrested in St. Joseph, Kansas. The charge was "possession of burglary paraphernalia" - they'd been caught with chisels, hacksaws, nitroglycerin funnels, gunpowder, and, in the court's words, "many sacks". Elmer, at this point a recently discharged soldier with an honorable record, pleaded with the judge that he and his friend were using these materials to develop a pedal-operated machine gun to sell to the Army. Whether or not this alibi was true, it seemed to match his Army records and his technical skills, and in January of 1911, he was found not guilty.

And whether or not he had intended to embark on a life of crime before this, a life of crime is exactly what Elmer McCurdy pursued from this moment on.

Elmer fell in with a group of people known as the "Yeegs". Yeegs were essentially people who lived as Hobos, scraping together a life along the rail lines, hopping trains, moving from town to town; but unlike most Hobos, Yeegs looked for criminal opportunities wherever they went. For Elmer McCurdy, the Yeeg life brought him to Oklahoma.

Elmer had skills that had great potential among the Yeegs, and his time in the Army meant that he could handle himself in dangerous situations. Although his career as a robber of banks and trains only lasted a few months, and was cut fatally short, when you take a closer look, you can't dismiss him as a bungler.

Robbing a train was not an easy thing to do. Trains were always at least partly armored, patrolled by guards, and sometimes armed with light artillery or machine guns. Some trains had better equipment than the Army! Guards were trained to shoot on sight whenever possible; and if they were outnumbered, it was a common tactic to barricade themselves within the armored cars of the train and fight off the robbers from there. If the guards could hold off the bandits long enough, they would eventually receive reinforcements, usually in the form of very heavily armed mounted security troops. Sometimes reinforcements would even come from the US Army. And even if you could make it past all of that protection quickly enough to outrun reinforcements, most train robbers lacked the sophistication to blow their way in to where the loot was.

The bottom line is that even trying to rob a train would far more likely get you killed or thrown in jail or run off than put any money in your pocket. And yet Elmer McCurdy did it; not just once but several times.

The key ingredient in his burglaries was nitroglycerin. Elmer's gang could get into armored cars and then blow off the doors of safes. If he were as sloppy and inept as his reputation, bringing something as incredibly unstable as nitroglycerin to a train robbery could have easily led to him killing or maiming himself, or killing innocent bystanders; and while it seems to have given him a dangerous reputation, there are no records of anyone getting hurt from his nitro use, including himself. As you recall, he didn’t lose his fingers until his corpse was on display near Mt. Rushmore.

Knowing the right amount of nitroglycerin to use is an extremely delicate science, and every robbery presented different challenges. In one instance, Elmer put together a crew that successfully stopped a train, and made it to a safe that contained $4,000 in silver coins. Elmer blew the safe open with his nitroglycerin, but he used too much, which melted not just the safe, but the silver inside. They improvised, scraping silver off the walls of the safe, and made off with about $450. That's over $12,000 in today's money - obviously not what any of them were hoping for, but far from a total bust.

And there's actually a smart reason why Elmer may have centered his criminal career around Oklahoma; he was in a part of the country where KATY trains passed through. Any trains that traveled along the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad were officially designated as MKT Trains, but KATY was the name that stuck. KATY Trains were high-risk and high-reward, they were known for carrying gold and other valuable metals, and for having wealthy passengers aboard. So Elmer McCurdy knew enough to put his business where the opportunity was - to strike a KATY train far from any major city meant fewer reinforcements to worry about.

And it was a KATY Train, passing near Okesa, Oklahoma, that he robbed on his final enterprise in life, on October 4th, 1911.

This wasn't a spur-of-the-moment heist. Elmer had been planning it for weeks. He'd received what he considered to be trustworthy intelligence that this train would be carrying more than the usual haul even for a KATY Train. He had heard that it was carrying a sum of over $400,000, which was alleged to be a payout from the U.S. Government to the Osage Nation of Native Americans. If Elmer and his partners had succeeded in grabbing loot like that, it would have stood as one of the biggest takes in the history of railroad heists.

But, by the time they got onboard and past the guards, there was no $400,000. Maybe it had been offloaded already. Maybe the schedule for moving it had changed, which wasn't uncommon. And maybe it had never been there at all - it wouldn't have been the first time that the United States Government broke its word to Native Americans.

Some versions of the story claim that foolish old Elmer McCurdy had chased the wrong train. But what the record seems to show is that he simply chased a story that turned out to be untrue. A rumor, a legend, a siren song of riches.

McCurdy's gang discovered that the train was mostly carrying mail. Their total take from the robbery was $46 in cash, an automatic revolver, two large jugs of whiskey, and the train conductor's gold watch.

The gang dispersed, hoping for the long arm of the law to tire out and look for easier prey. McCurdy took refuge in a barn near Bartlesville, Oklahoma, which belonged to an old friend. He had brought the stolen whiskey with him and drank until he blacked out. What he didn't know was that a $2,000 bounty had been placed on his head, and the police bloodhounds had found his trail. According to most accounts, when local Sheriffs entered the barn, he staggered to his feet, but didn't get a shot off. The so-called "Bandit Who Wouldn't Give Up" never got the opportunity to give up, as one shot to his chest ended his life. The Oklahoma Territorial Museum, which has a rich trove of information about Elmer McCurdy's life and afterlife, still has the Luger pistol which fired the shot.

If you only judge the criminal escapades of Elmer McCurdy by that ending, it does sound comical, bordering on the pathetic. Dying alone, drunk, and a failure. But in just nine months of stealing, McCurdy had made off with, in today's dollars, at least $25,000. That's better than an entry-level job, and would have been a much better living for him than scraping out itinerant work along the rail lines. Who knows what he might have pulled off with more time to refine his use of nitroglycerin?

It’s unlikely a drunken bungler could have successfully breached the defenses of a KATY train, even if the loot they sought turned out not to be there. McCurdy doesn't belong in the top tier of Western desperadoes; but taking all this into account, it wouldn't be right to call him a fool either.

***

PART FOUR

In the classic Western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, a newspaper reporter says: "This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." Hollywood is a business that endures because it gives the audience what it wants; and if that audience wants sensational thrills, perfect heroes in white hats, and lethal justice for people who stray from decency, that's the version of the story Hollywood knows how to tell. It's hard to tell the truth of a real life in just a couple of hours; at least, it's hard to make it entertaining.

It's ironic to me that Elmer McCurdy became a train robber eight years *after* the movie "The Great Train Robbery". The Old West was already fading; even as the legends about it were getting ever-more-spectacular. The population of Western territories was growing, along with it, all the modern infrastructure of white civilization, after decades of brutally driving the Native American tribes into submission and exile. The railroad barons had seen their monopolies broken, most of the rogue Confederate soldiers who had spread terror all over the West were either captured or dead. Modern policing was replacing the mythical frontier Sheriff, if he had ever been real. Automobiles were appearing on the roads next to the horses. It could be fairly said that Elmer McCurdy was as close to John Dillinger as he was to Jesse James; but once you hear that he robbed trains, it's hard to picture him in anything but a cowboy hat.

In his life, I see a young man with both talents and flaws, someone who strived, struggled, and was blown about as we all are by some of the larger forces in the world, like economic calamity, growing up without a father, struggling with an addiction to alcohol. Undoubtedly a criminal, probably an angry and a desperate one, but not a fool, and far from the cold and sadistic villain who pointed his gun at the audience in "The Great Train Robbery". The life of the real Elmer McCurdy holds complexities we don't like to hear about when it's time for a good Western yarn.

From the first time his dead body was embalmed and propped up in the undertaker's shop, it was treated as a symbol rather than a person, a trigger for a collective act of storytelling, of mythmaking, that grew with the imagination of a long line of hucksters and entertainers who knew what their audiences wanted the most. The story was worth a lot of money to a lot of people, and, it must be said, gave a little thrill of entertainment to countless audiences over the years.

None of them ever knew the real Elmer McCurdy the way we've tried to know him in this podcast. But even if they'd been willing to come with us on the Dark Path in order to find the facts, I think they would have printed the legend. That was the number one priority from the very first day of business at Nestor Studios, across the street from Gower Gulch, where the dream factory of Hollywood was born just twenty days after the death of Elmer McCurdy, future Hollywood celebrity.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5 star rating wherever you’re listening. Lastly, thank you for listening. You have more choices than ever about where to spend your time. I’m grateful that you’ve chosen to spend some time here exploring the Dark Paths of the world together. And don’t hesitate to reach out via email – explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you. I really would!

Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle, and he and our lead researcher Alex Bagosy were instrumental in preparing this week's script with me, so a big thank you to them.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me, your host, MF Thomas. Until next time, good night.

Listen to learn more about

Elmer McCurdy—a train robber who was killed in 1911 after attempting to steal $400,000 from a train in Oklahoma.

When a TV crew preparing to shoot an episode discovered that the mannequin they thought was just a prop was actually a human corpse.

The history of Hollywood and the events of Elmer McCurdy’s life that led to his death.

The implications of how easy it can be to dehumanize others.

References

“The Long, Strange, 60-Year Trip of Elmer McCurdy.” Snap Judgement. National Public Radio, npr.

Freak-O-Pedia, “Mummy in the Dark.” Sideshow World, John Robinson.

Music

What We Dream, Matt Wigton

Brenner, Falls

Unchained, Federico Ferrandina

Finally Home, Brent Wood

Autumn Drive, Brent Wood

Crowheart, The Realist

Perfect Spades, Third Age, Nu Alkemi$t