Episode 13: The Original Foo Fighters— The Legend of the Nazi UFO

As well-documented as things are, there’s so much left that’s unknown. And the speculation about just what the Nazis could be capable of didn’t start in the aftermath as historians and scientists worked to put together a record of it all. It had an impact on the battlefield at the peak of the fighting.

Maybe the best way to capture this dark path of imagination where I found myself on this dark and stormy night, of wondering how far the reality of Nazi ambitions went, and how these other legends about them could have evolved, is to tell you the story of the Foo Fighters. And no, I’m not referring to the band from Seattle that was just voted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I’m referring to how they got their name. It’s a story that involves a Chicago comic book artist, a 19th-century fantasy novel, and one of our favorite things here at My Dark Path – strange lights in the sky…

LISTEN OR READ THE FULL SCRIPT BELOW TO LEARN MORE ABOUT:

Project Bluebook: the United States Military investigation into flying saucers and other unexplainable phenomena

the extraterrestrial kraut fireballs that troubled WWII pilots

The Nazi's Flying Saucer Project

How The Foo Fighters got their name

The origins of the phrase, "a dark and stormy night" and "the pen is mightier than the sword"

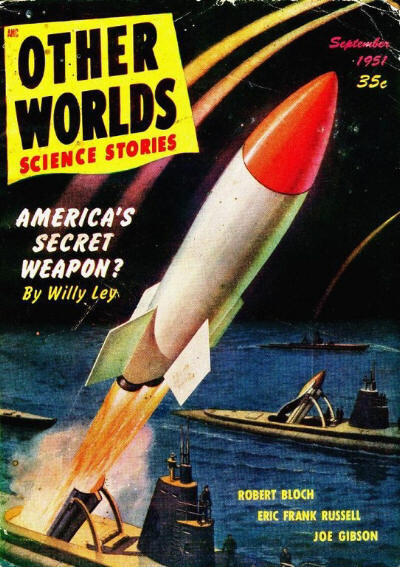

Cover of Other Worlds, September 1951 by William Ley

Possible UFO sighting

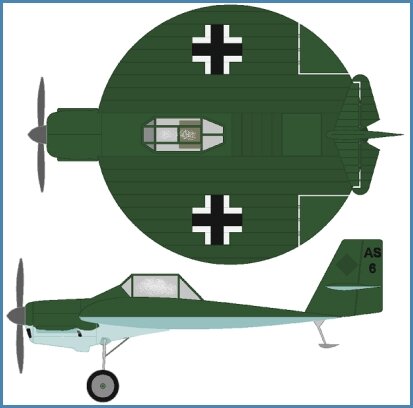

Arthur Sack’s A6 V1

P-61 Black Widow- a night fighter during WWII

Robertson Panel member Luis Alvarez.

Robertson Panel consultant J. Allen Hynek

Wernher von Braun (center), Dr. Heinz Haber (left), and Willy Ley,

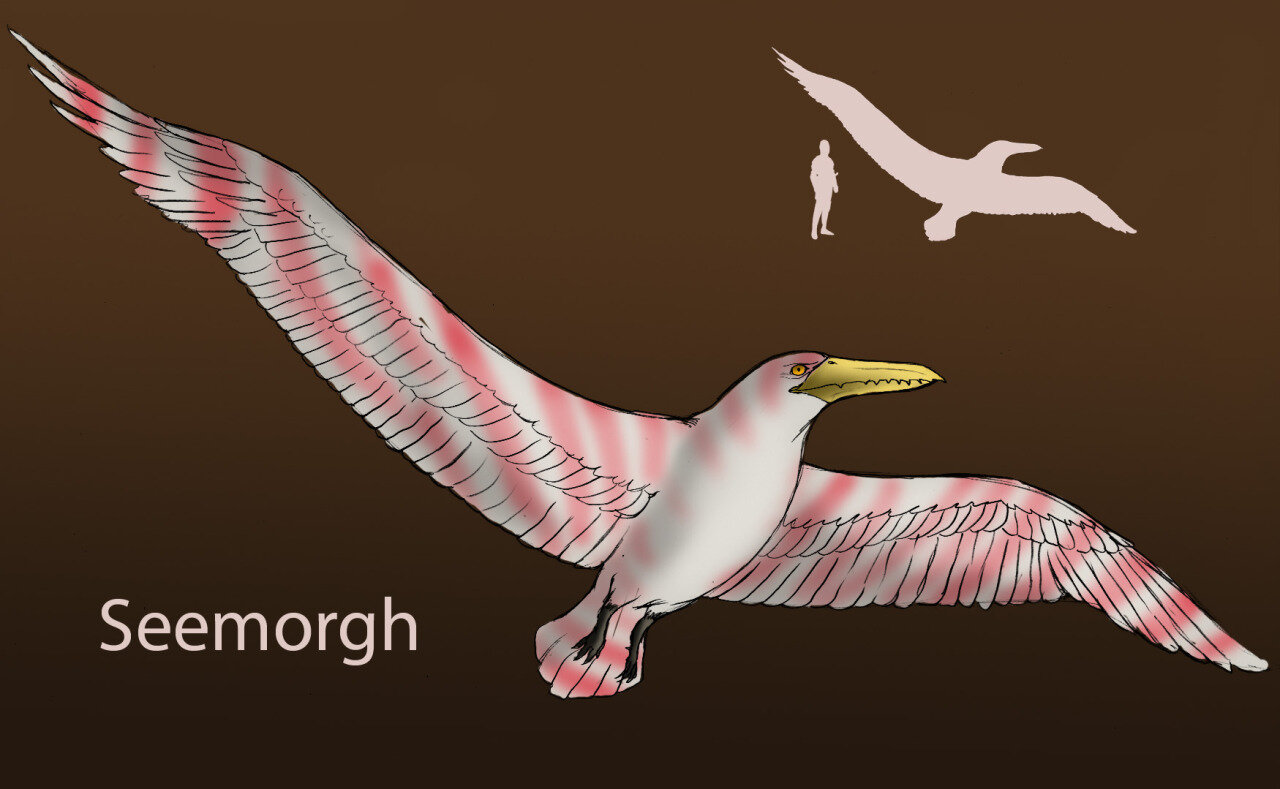

Vrill depiction by Phillip Price based on the novel "The Coming Race"

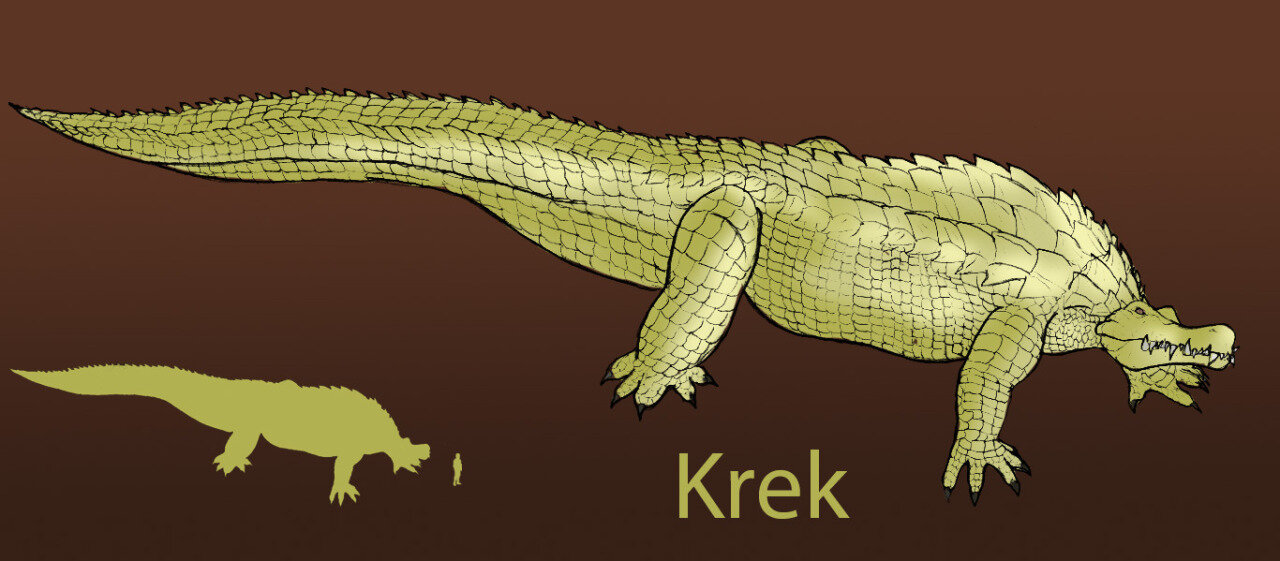

Hollow Earth Creatures Depiction by Phillip Rice based on the novel "The Coming Race"

Hollow Earth Creatures Depiction by Phillip Rice based on the novel "The Coming Race"

Nazi Foo Fighters Photo taken Inside the Roswell Museum

SOURCES:

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING:

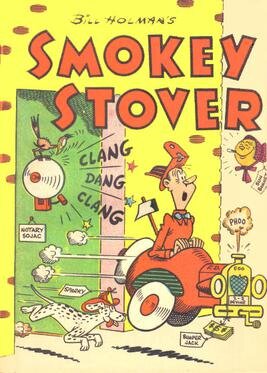

Bill Holman photos with permission of www.smokey-stover.com

Smokin' Rockets by Patrick Lucanio

http://www.luft46.com/misc/sackas6.html

Pseudoscience in Naziland by Willy Ley

The Durant report of the Robertson Panel proceedings

http://ufxufo.org/german/sack.htm

Édouard Riou, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

MUSIC

Darker Days, Alternate Endings

Perfect Spades, Third Age, Nu Alkemi$t

IMAGES

Art inspired by The Coming Race by Phillip Rice: On Twitter @spearhafoc_

Full Script

INTRODUCTION

It was a dark and stormy night; and I was getting ready to start writing my first novel. That phrase, “It was a dark and stormy night,” is so often repeated that it’s become a cliché describing overheated and melodramatic opening sentences in novels. There’s a reason why we’re opening this episode with it; stick around and you’ll learn all about it.

But for my own novel, Seeing by Moonlight, I was immersing myself deeply in the rumors and theories published about secret, advanced Nazi weapons programs during World War II. It’s a subject that has attracted countless authors over the decades, and the more I read, the more I understood the obsession. Even the claims that were too outlandish to seriously consider were, nonetheless, intoxicating. When I wasn’t working on the book, I caught myself speculating about the dangers the human race averted by defeating this monstrous regime.

My own book is fiction, and we don’t pretend it’s anything else; but it drew heavily on the speculations and legends that are well-known in this particular field. I love telling a good story and history is full of them, but I think even when you’re just writing a fictional novel to entertain, it’s important to recognize where conjecture is taking over. The human mind has the incredible capacity to build a bridge to just about any idea, and make it sound compelling and well-reasoned. But the dark side of that gift is that it renders us vulnerable to conspiracies, cults, and other versions of so-called magical thinking.

I read theories about Nazi time machines, about moon bases, about submarines traversing secret tunnels under Antarctica. It makes for a hell of a story; and I think part of why I and so many others dwell on it is that it's a historical fact that German scientists were on the forefront of aviation and rocketry technology, putting new inventions on the battlefield that the Allies couldn’t duplicate. And we know that they had even more radical ideas on the drawing board when they were finally defeated; our episode about Peenemünde talks about that and we’re going to continue exploring it.

But as well-documented as these things are, there’s so much left that’s unknown. And the speculation about just what the Nazis could be capable of didn’t start in the aftermath as historians and scientists worked to put together a record of it all. It had an impact on the battlefield at the peak of the fighting.

Maybe the best way to capture this dark path of imagination where I found myself on this dark and stormy night, of wondering how far the reality of Nazi ambitions went, and how these other legends about them could have evolved, is to tell you the story of the Foo Fighters. And no, I’m not referring to the band from Seattle that was just voted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I’m referring to how they got their name. It’s a story that involves a Chicago comic book artist, a 19th-century fantasy novel, and one of our favorite things here at My Dark Path – strange lights in the sky…

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 13: The Original Foo Fighters.

PART ONE

In the 1930’s, a Gallup Poll revealed that Americans considered the most important section of the newspaper to be the comics section. In the battle for supremacy among media titans like William Randolph Hearst, every major city had multiple newspapers, and people would often buy a paper based on whether it carried their favorite comic. In 1945 there was a long newspaper strike in New York, and Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia actually went on the radio to read the comics, so the city’s children wouldn’t miss out on their favorites.

Comic strips weren’t all just silly gags, some of them were detective thrillers, others were soap operas. Comic sections could take up 16 or even 24 pages, more than the front page section of a lot of major newspapers today; and comic strip characters like Blondie and Dick Tracy could grow into multimedia phenomena. People would clip and share favorite strips to one another the way we send memes and videos on the Internet today.

In 1935, Chicago cartoonist Bill Holman debuted a comic strip called Smokey Stover, that told the absurd adventures of a firefighter. Part of Holman’s style was the use of puns and nonsense words. Often, these words took on a life of their own. His favorite was the word “Foo”, which could show up anywhere in a Smokey Stover adventure – on a menu, a sign, as a substitute for another word in dialogue. Smokey’s motto was “Where there’s foo, there’s fire”. If there’s a single reason why Holman started using this made-up word, we don’t know it – he told several different stories, probably having a big laugh at the idea that the word needed explaining. Comedy obeys its own rules.

It caught on with others and became a slang word whose meaning was its meaninglessness. It even showed up in a couple of Looney Tunes adventures. And Smokey himself often described his job not as a fire fighter, but as a “foo fighter”.

When American aviators went overseas to fight in World War II, they often decorated their planes with images of pinup girls and cartoon characters. Smokey Stover was a popular image, and it’s among our brave Army Air Force servicemembers that “Foo” transformed – from a meaningless gag word, to a matter of national strategic interest.

In the fall of 1944, pilots and aircrew, while flying missions over Western Europe, reported seeing lights in the sky around them. They described the lights as fiery, glowing red, white, or orange; they said the lights seemed to follow their formation no matter how difficult the maneuvers, as if they were controlled by some intelligence. They could also zip away at impossible speeds, or simply disappear.

Many reports on this phenomenon used the term “Kraut Fireballs”. There was immediate speculation about it being an advanced German weapon program. It was a reasonable leap to make – just weeks before, the Nazis had put their terrifying new invention, the V2 ballistic missile, into battle; and it was well known that somewhere, German scientists were working on the atomic bomb. Maybe this was yet another, new power they had harnessed.

But a different name took hold starting on November 27, 1944, during a debriefing at the 415th Night Fighter Squadron. The unit’s intelligence officer, Fritz Ringwald, was interviewing Donald J. Meiers and Ed Schleuter. As the two men struggled to describe the strange light they had both witnessed, Meiers, a native of Chicago, reached into his back pocket, pulled out a copy of his favorite comic strip from back home, slammed it on the desk, and said “It was another one of those foo fighters!”

Actually, Meiers added an additional “f-“ word before “foo”; but it’s not a word we use on this podcast.

A reporter from the Associated Press met up with the 415th and filed a story on the unusual sightings. He used the cleaned-up term of “foo fighters”; and it caught on as the name – it was even the subject of an article in Time Magazine that January.

Now the Allied pilots didn’t know that German pilots were also reporting strange lights in the sky as they flew their missions. But neither side ever reported the lights behaving in any hostile way. Mysterious illumination was also happening on the other side of the world, as America battled Japan for supremacy in the Pacific; but those lights had their own peculiar appearance and behavior.

Remember, we didn’t yet have the term “U.F.O.” The Kenneth Arnold sighting, the Roswell incident, these moments that triggered the era of the “flying saucer” didn’t happen until 1947. And these weren’t speculated to be alien in origin. That they might be Nazi-controlled was frightening, and realistic, enough.

And it just so happens, at least one Nazi actually was building a flying saucer.

Back in 1938, before the outbreak of the war, Germany held a contest – the Reich-Wide Contest for Motorized Flying Models. The contest was held in Leipzig, and was an opportunity for hobbyists and enthusiasts to test out their models for next-generation flying machines. One of the models was entered by a farmer named Arthur Sack, who had created an unusual design with a single, circular wing. And unlike many of the models put to the test that day, it actually took off and flew.

His test flight just happened to be witnessed by Ernst Udet, a decorated pilot who was the chief of armaments procurement for the Luftwaffe. He was particularly consumed right then with the problem of creating light aircraft which could take off from very short airstrips for reconnaissance or attacks against ground targets. Arthur Sack’s disc-shaped model plane just happened to resemble some of the prototypes that Ernst Udet had seen in action and, impressed, he encouraged Arthur to continue his experiments.

Arthur Sack worked for five years, producing five models of increasing complexity; until finally, in 1944, he built the real thing – the Sack A6 V1. Circular, 21 feet in diameter, it stood just 8 feet off the ground, and could only fit a single pilot. From the side, you might mistake it for any combat fighter of the 1940’s. From above, though, it was a circle, with a propeller on one end. A flying saucer.

The bad news is that it didn’t actually fly. Again and again, Sack tried to get it off the ground, but only managed to make short hops. He kept trying, and from what we can tell, the Nazis thought there was some promise in his design; but they refused his request for an elite test pilot, and he refused to try some of their suggested modifications. The only A6 V1 circular aircraft ever built was damaged in an Allied strafing run, and, as far as we can tell, Sack abandoned the project after that.

It’s provocative, though, to think that this idea didn’t come from any of the best and brightest scientists working for Werner Von Braun or others in Nazi Germany, it came from an ordinary farmer who was trying to help the Reich. And with the Luftwaffe keeping such a close eye on his research, is it really lost to posterity? Did they really abandon the idea completely? Arthur Sack’s invention figures prominently in the speculation about so-called Nazi UFO’s, but we do know this – even if he had put it in the air, it didn’t bear any resemblance to what the Americans were calling the “foo fighters” appearing in the skies around their planes.

With the war entering its final stages, it didn’t seem to matter as much what the Foo Fighters were. But the reports compiled by the military on the phenomenon resurfaced just a few years later, in the offices of a relatively new department in the U.S. Government – the Central Intelligence Agency.

PART TWO

The C.I.A. was founded in 1947 to serve as a permanent institution for foreign intelligence and covert action. The United States was an unquestioned global superpower after World War II, and the C.I.A. was going to play a role in protecting its interests and expanding its influence. Its early track record was not great – as just one example, it missed that the Soviet Union had developed the atomic bomb. But the government had a lot of ideas; things they wanted to use this young agency for, so their resources kept growing.

On the night of July 19th of 1952, there was a rapid-fire series of strange sightings in the sky and on air traffic control screens in Washington, D.C. It set off a panic that made it all the way to the White House. Multiple blips were appearing on radar, moving erratically; an airman at Andrews Air Force Base reported an orange ball of fire, soaring through the air at incredible speed. An airline pilot at National Airport, sitting in the cockpit waiting for clearance to take off, told his control tower that he saw a series of six white lights close on his position, then rapidly change direction and streak out of sight.

Jets and bombers were scrambled to intercept signals, only to find nothing there when they arrived. The sightings went on for nearly six hours, and word spread quickly through the media. All the way out in Iowa, the Cedar Rapids Gazette published the headline: “SAUCERS SWARM OVER CAPITAL.”

Amazingly, exactly one week later, the strange events repeated themselves. On the night of Saturday, July 26th, there were another series of unexplained radar signals, pilots reporting white lights streaking through the sky. The pilot of an F-94 Starfire jet claimed that they were chasing one of these lights, but even at the jet’s maximum speed, he couldn’t keep up.

The leading theory for the false radar signals was a temperature inversion, clashing layers of cool and warm air, a common meteorological phenomenon. But the experienced radar operators on duty that night had never seen air temperature create so many solid, long-lasting radar signatures.

By the time it was all over, hundreds of sightings had been reported in and around our nation’s capital. At one point, the objects even appeared to fly over the White House. Facing another nationwide round of panicked headlines, President Truman ordered that a call be placed to Air Force Captain Edward J. Ruppelt. You might remember his name from our episode about early UFO sightings in America – he was the head of Project Blue Book, the military’s official investigation into flying saucers, lights in the sky, and any other phenomenon that couldn’t be explained.

Incredibly, Ruppelt had actually been in D.C. on the first weekend of sightings; and had requested a car so that he could visit the locations and interview people involved. But the military denied his request – he didn’t hold a high enough rank to qualify for a staff car. They suggested he use his own money to hire a cab. We can’t say whether or not this reflected a certain institutional disrespect for Ruppelt’s work, but we do know that he didn’t hire a cab.

Ruppelt was the one to offer the theory about temperature inversion, and it was also suggested that an unexpected meteor shower could have been responsible for some of the eyewitness accounts. Days later, the Pentagon held their largest press conference since World War II, attempting to calm the nation.

But behind the scenes, the CIA saw a reason to be very concerned, and to study the issue further.

***

Here’s an excerpt from an internal C.I.A. memo, dated August 19th, 1952. Quote: “This whole affair has demonstrated that there is a fair proportion of our population which is mentally conditioned to acceptance of the incredible.” End quote. Whether you agree with that judgment or not, it’s a fair description of what the C.I.A. was worried about. Even if there wasn’t any such thing as UFO’s, it was a national security concern that a sudden surge of sightings could flood communication channels, leading to panicked civilians, and military aircraft chasing radar phantoms. If an enemy like the Soviet Union saw how our attention could be distracted with fears of an alien invasion, then the next set of sightings and false reports might not be so accidental.

The C.I.A. decided that it needed to investigate U.F.O.’s – not because they believed there was any chance they were real, but because they wanted to find quick ways to identify and explain away these false signals before they could cause any mass confusion. While Project Blue Book was attempting to gather data without jumping to any conclusions, the C.I.A. was starting from the presumption that there was a simple Earthly explanation, if we just knew how to find it.

But in a matter of just a couple of months, they were hitting a wall. There were too many sightings that couldn’t be explained as a meteor, or a weather balloon. So, they did what any good government agency does in a crisis – they put together a committee. It held its first meeting in January of 1953, and it was called the Robertson Panel.

Howard P. Robertson was a Professor of Mathematical Physics at CalTech and Princeton Universities. He was one of America’s big brains in the mid-20th century, studying quantum mechanics and the uncertainty principle, contributing to the theory that our Universe is still expanding. He also had a long track record of helping his country, consulting for the Secretary of War during World War II and serving on the National Defense Research Committee, the precursor to the Manhattan Project. He even helped interrogate the German scientists who had worked on the V2 rocket program at Peenemünde, because of his expertise, and the fact that he spoke fluent German.

Robertson assembled his committee to fulfill the CIA’s request – it included a nuclear physicist, a future Nobel Prize winner, a CIA missile expert, and none other than J. Allen Hynek, the astronomer who worked with Project Blue Book and later founded the Center for UFO Studies.

In a way, it’s sort of funny just how much expertise was gathered in one room, and how little scientific data they had to work with. There were blurry photographs, snippets of film, vague official reports. Captain Ruppelt brought 23 of what he called Project Blue Book’s “best cases” – the ones that seemed the most resistant to natural explanation. They also discussed the Air Force reports on the Foo Fighters. It was generally agreed that if the term “flying saucers” had existed in 1944, these sightings probably would have been identified by that name.

The Robertson Panel did their best. They reviewed the eyewitness accounts, they scrutinized the photographs; they even spent a long period of time watching slow motion film of seagulls in flight, in order to see if the way they moved, and the way the light reflected off of them, might resemble some of the footage they’d seen.

In the end, they weren’t able to find quick methods to explain away these sightings. They weren’t ready to believe any extraterrestrial theories, so they were back to their original question – how could they prevent America’s fascination with UFO’s from being used against it in the Cold War? Flying saucers were so exciting to Americans that they were showing up on movie screens and in sci-fi books, UFO societies were forming around the country so that amateur enthusiasts could conduct their own investigations.

After the summary reports of the Robertson Panel were compiled, the C.I.A. proposed two courses of action that, put together, proved to be absurdly self-defeating. First – they recommended a coordinated public messaging campaign designed to assure the public that there was no such thing as UFOs. Second – they would start spying on groups of UFO enthusiasts. Just to make sure they weren’t being infiltrated by Soviet agents, you see.

A government aggressively pronouncing that there’s nothing to see here while also spying on its own people about that very subject – I can’t think of a better recipe for inflaming peoples’ belief that there was something the government wasn’t revealing.

I mentioned that, during the war, the leading theory about the Foo Fighters was that they were an advanced Nazi weapon. Now, after the war, they were being revisited to consider whether or not they the creation of some non-human intelligence. Maybe it won’t surprise you to learn that there are plenty of people out there who have asked the question – what if they were both?

PART THREE

“The German tends to resort to magic, to some nonsensical belief which he tries to validate by way of hysterics and physical force. Not every German, of course…It was the willingness of a noticeable proportion of the Germans to rate rhetoric above research. and intuition above knowledge, that brought to power a political party which was frankly and loudly anti-intellectual.”

Those words were written by Willy Ley, a German rocket engineer who had left Germany in 1937 as the Nazis were growing in aggression and ambition. He published an essay called “Pseudoscience in Naziland” in, of all places, Astounding Science Fiction magazine. I appreciate the fact that a magazine dedicated to wowing its audience with fantastical tales also understood the importance of standing up for scientific truth in the face of fascism; of drawing a bright line between fiction and non-fiction. It makes me proud to call myself a sci-fi author.

Ley provides detailed memories of the atmosphere of magical thinking that pervaded German culture in the years between the World Wars. It’s just one person’s eyewitness account, but it tracks with what we know about the Nazis’ obsession with finding so-called “proof” that they represented the Ubermensch, the superior Master Race destined to rule humanity. It’s why the SS had Archaeology teams searching the world for artifacts that would prove their connection to the mythical and perfect Aryans. We’re doing some digging of our own into the stories of those teams and look forward to sharing what we learn with you.

Willy Ley’s essay describes groups meeting in Berlin for pseudo-scientific lectures which claimed that every man was biologically part angel; and that the Master Race, naturally, had the highest percentage of angel biology in them. He talks about Nazi Naval Officers believing they could find enemy battleships with the use of a magic pendulum. A former mining engineer named Hanns Hörbiger claimed he had solved all the riddles of the Universe with intuition and dreaming – he declared that photographs of stars in the Milky Way were fake, and the solar system was actually surrounded by giant ice blocks floating in space. He attracted thousands of fanatical followers; one of them wrote a threatening letter to a government scientist. “once we have won,” it read, “you and your kind will go begging.”

There’s one paragraph in Ley’s essay which has been the subject of speculation ever since it was published. He says that there was a group in Berlin which called itself Wahrheitsgesellschaft – the Society for Truth – which dedicated itself to the search for Vril. They believed that Vril was the secret power that had allowed the British to colonize the world, and ancient Rome to build its empire. And with Vril, they believed, they could become superhuman, and create weapons that would let them rule the Earth.

What is Vril? I’m glad you asked…

***

Edward Bulwer-Lytton was a politician and nobleman in 19th-century England who was heavily-involved in global affairs of the day – but he was just as well known in his time for his unusual lifestyle. His mother cut him off from much of his family’s wealth, and he refused many high appointments presented to him. At one point he was even offered the opportunity to be the King of Greece, and said no. He wanted to make sure he always had time for his favorite activity, and the real source of his wealth – his writing. In the midst of serving in Parliament, Bulwer-Lytton was also a novelist, and a sensationally-successful one.

It was Bulwer-Lytton who coined the phrase “It was a dark and stormy night”; that’s why we started this episode with it. It appeared in a novel of his called Paul Clifford, and to this day, there’s an annual contest in writing circles, the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest – that challenges writers to come up with the most outrageously-terrible opening sentence for an imaginary novel. You should look it up, it’s always good for a laugh.

But at the time, the popularity of his works and his constantly scandalous private life meant that he was one of the most famous contemporary authors in England, and he was treated seriously in the literary world. He even convinced Charles Dickens to change the ending of Great Expectations to make it happier.

In 1871, as his health was diminishing, Bulwer-Lytton published a book called The Coming Race. In an unusual turn for him, he published it anonymously. That may, in part, have been a trick of publicity. The book is written in the first-person, and claims to be the account of an unnamed, wealthy young American explorer who descends deep into a chasm exposed by a mine shaft, and finds himself in an advanced underground civilization.

The beings that live there called themselves the Vril-ya. In ancient times they lived on the Earth’s surface, before fleeing into a network of natural underground tunnels to escape a great flood. Now deep below the surface, they have built a miraculous, utopian society using the power of the substance they call Vril.

Vril is a fluid that contains limitless energy. It can be used to fuel advanced technology, and beings of great willpower and spiritual strength can even learn how to control it. A Vril user can read minds, heal from wounds and disease, even level entire cities with a power like lightning. Some of the Vril-ya carry what they call a “Vril Staff”, a wand or rod that harnesses Vril energy for its wielder. And if you just pictured a lightsaber from Star Wars, it’s okay – I did when I first read it, too.

The nameless narrator of the book lives among the Vril-ya, learns their ways, and falls in love with the daughter of the local magistrate, only to be chased back to the surface because their love is forbidden. The book ends with a warning that these powerful beings are growing in number, and soon there won’t be enough room for them even in the vast secret tunnels below the Earth. The Vril-ya, he claims, will come to the surface to conquer humanity.

The Coming Race fits in at a key juncture in the evolution of sci-fi literature. The idea of explorers descending deep below the surface and finding hidden wonders was already pioneered by Jules Verne in Journey to the Center of the Earth, and many years later, when HG Wells published The Time Machine, critics at the time noticed the section where the book’s time traveling protagonist lives among the futuristic Eloi and Morlocks, comparing it to Bulwer-Lytton’s work.

Both Verne and Wells are much better remembered to modern readers; but the influence of The Coming Race is just as great, even if the connective threads aren’t as obvious. In particular, its original, anonymous publication put it in a grey area between fiction and non-fiction, and some people seem to have been so captivated by the idea of Vril that they genuinely believed it existed. In that essay I told you about by Willy Ley, he claims that the so-called “Society for Truth” even knew that The Coming Race was actually a work of fiction; but they simply claimed that it was presented as fiction in order to mislead people.

We don’t have any other documentation verifying the existence of the Society for Truth, or exactly how they went about looking for Vril. It could be simply that they were amateurs consumed by the same fever that possessed so many in Nazi Germany, looking for a way to connect their great destiny with the superior races and empires of human history.

It reminds me of another famous saying coined by Edward Bulwer-Lytton: “The pen is mightier than the sword”.

PART FOUR

The reason why stories like the Foo Fighters and the 1952 sightings over Washington, D.C. remain so fascinating and frightening is that nothing human-made could move as fast or maneuver so strangely as those lights in the sky seemed to move. If it was indeed some form of technology, it would have to be created by people who had advanced far beyond humanity, people who could control mighty power sources we couldn’t understand.

Before we understood what oxygen was and how combustion worked, scientists speculated that there was a special substance that created fire. They called it phlogiston, and their theory was that phlogiston escaped into the air when something was burned; which is why it couldn’t be reconstituted later.

The theory turned out to be somewhat backwards, but I’ve always liked the idea of phlogiston as a stand-in for a process we don’t understand yet. You might look at Vril in much the same way – if we can’t understand how it’s possible, maybe it’s powered by Vril. If we can’t pinpoint who made it, maybe it was people who could control Vril. Until we know the real answer, we might as well call it that. Like the term U.F.O. itself, it represents the unknown.

But there’s more than that going on in the story of the Original Foo Fighters. It isn’t just the unknown, it’s the powerful human need to find answers, even if we have to imagine them before we can explain them. It’s been the province of science fiction authors from the very beginning to imagine devices we can’t make yet, discoveries we can’t yet reach. How many pieces of technology did we see on old episodes of “Star Trek” which are a part of our daily lives now – tablet computers, wireless medical scanners, 3-D printing?

Even when the CIA was trying in its own, clumsy way to dampen our curiosity, it only intensified our need to know. These sightings that are so beautiful and ominous and strange, they stick with us because our curiosity can’t be fully suppressed. And even an author spinning out a fantasy on paper can capture our imaginations; convince us that, even though it comes in the form of a lie, it might be a lie that points the way towards truth.

The most common consensus in science for what happened in the skies over Europe, for those strange lights that became known as Foo Fighters, is that it was probably an example of what’s known as St. Elmo’s Fire. St. Elmo’s Fire is a glowing plasma created by an atmospheric discharge – when electrical energy begins to gather around a long shape like a lightning rod or a ship’s mast. It’s named after the patron saint of sailors, and we have references going back thousands of years that describe sightings of it. Julius Caesar witnessed it. St. Elmo’s Fire was seen dancing atop the Hippodrome when the Ottoman Empire laid siege to Constantinople; it was interpreted by the Christians as a sign that their God would destroy the Muslim Army.

The 15th century Chinese Admiral Zheng once wrote in his journal: “…when there was a hurricane, suddenly a divine lantern was seen shining at the masthead, and as soon as that miraculous light appeared the danger was appeased, so that even in the peril of capsizing one felt reassured and that there was no cause for fear.”

Because St. Elmo’s Fire is caused by a build-up of electricity, it be used as an early warning that lightning is about to strike; that’s why sailors tend to take it as a good omen that someone is looking out for them. We don’t completely understand it, but it lets us know that some mighty power is at work. Call it basic physics, call it Vril, but maybe Smokey Stover had the best way of describing it: Where there’s Foo, there’s Fire….

***

One final postscript – this episode has been in the works for months, long before the recent story on 60 Minutes about modern military investigations into what they’re now calling UAP’s – Unidentified Aerial Phenomena. Trust me – the whole team here took great interest in that story and we’re following it in order to see what we can incorporate into future episodes. Just take it as a sign that the search for Foo continues.

END

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Emily Wolfe and Evadne Hendrix; and our audio engineer is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by our senior story editor, Nicholas Thurkettle. Our lead researcher is Alex Bagosy; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.